Cult Icon

2585 replies · 37567 views

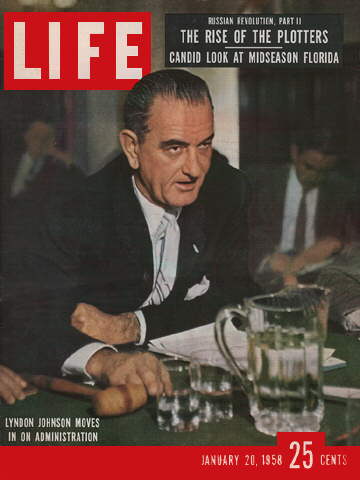

on LBJ and reading

-LBJ dropped out of Georgetown Law School after two months- he couldn't stand the reading. He could not stand learning latin, legal history and philosophy.

-LBJ never read books, which vexed Lady Bird Johnson, a college educated woman. He also exposed himself as less intellectual when he was around lawyers, scholars and ivy league types. He just worked 100-hour weeks and focused on things he needed to do as a Congressman, which involved amassing immense practical/technical knowledge as a politician and executing political operations.

-Lady Bird Johnson entertained Johnson's constituents- she spent all her free time preparing. She was enormously well read about DC, culture, and history.

-LBJ's weak knowledge in non-practical areas- eg., Military history, combat weapons, operations, and tactics, philosophy, culture, sociology - perhaps doomed the US to his disastrous decision to escalate the war in Vietnam.

on Robert Moses and reading

-In his 44 year career, Dr. Moses moved beyond his Ph.D in political science to amass such immense knowledge in engineering, architecture, and law that specialists in the field were impressed. He was considered a genius.

* Moses quote "you can get a lot done in the world if you let other people take credit for it".

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v38/n06/jackson-lears/capitalisms-capital

----

*A key of LBJ's congressional victory was his aggressive campaigning in dirt poor and unpleasant areas- his political enemies were too lazy and repelled to do this.

-Also key was timing: Retirement and a vacant congress seat.

*LBJ's health suffered, which lead to his pre-mature death later in life. Besides stress related ailments, he would lose up to 40 pounds during his first congressional campaign. 140 lb, 6 foot 3.

-LBJ connects with a media mogul, and their years of friendship ensures a stream of pro- Congressman Johnson propaganda; his newspapers would continue to aid LBJ in his re-election.

*In Washington, LBJ routinely broke the rules (written and unwritten) if they got in the way of his purposes; Moses had open contempt for the law and would boast that "nothing I have done has been tainted with legality".

Among veteran, older politicians:

-"his efforts to dominate other men succeeded with 1-2 fellow Texans (quiet, unassertive) aroused only resentment". "insincerity" "He would tell everyone what he thought they wanted to hear. As a result you couldn't believe anything he said". But LBJ was shielded by his protector, Rayburn.

-LBJ courted influential citizens from all across the state.."he courted the right people in the right places all over the state".

-"Johnson turned down wealth and jobs in the pursuit of some unstated ambition"

-On coming to Congress/Washington- he found the House (435 men) run by seniority and a trap. Ability, maneuvering could not get a man up top; just decades of service. There were senile congressmen that never got the top positions, and retired in their 80s.

LBJ pg. 605

-Congressman Johnson would go to extraordinary lengths to not reveal his opinion. He wouldn't take a position on an issue or say anything of substantive nature. For 11 years, he avoided speaking and when he did, he said what the other person wanted to hear. LBJ stood for nothing. By keeping silent, LBJ was taking a path to power. He did not aspire to become speaker of the house.

-He was always aware of the fact that he was responsible for what he said. He was always aware that what he said might be repeated or remembered. Who could foresee the turnings of so long of a road?

-LBJ liked appealing to mutual hatred of someone else or something, in prviate.

-LBJ's behavior was noticed by other congressmen- with scorn. LBJ avoided being around the 'small fry', and aimed his activities on the 'big fry'.

-This was always part of LBJ's tactic: If he couldn't lead, he wouldn't play. He knew that he was too junior and inexperienced to hold much sway over veteran Congressmen with decades of experience.

-Since, LBJ had less power in this new environment...his old tactics were not as effective. The "johnson treatment" backfired on some men, as they were repulsed by this. it earned him unpopularity with some persons.

-Johnson did not give up in these years- he was waiting and plotting for strategies that would lead him to seize power as a Senator

- His volume of personalized correspondence was prodigious

- making seemingly trivial positions into important sources of political power.

"Roosevelt's letter was packed with Roosevelt charm, but for Jack Garner the charm had long since worn thin"

-as a storyteller, the intensity of Johnson's stories made others pale, to cement his social leadership. *johnson prepared for them well.

"Through federal contracts, Johnson had made

Brown rich, and given him the chance to build the huge projects of which he had long dreamed, and Brown had ordered up contributions from dozens of subcontractors on Brown & Root dams and highways and had, in giving from his own firm’s coffers, gone to the edge of the law and, some Internal Revenue Service agents were later to contend, over that edge into the realm of fraud in order to finance Lyndon Johnson’s ambition. Brown wanted to make more millions, and to

build projects even huger. Representative Johnson had brought Brown & Root millions of dollars in profits. What might Senator Johnson be able to do? Now Herman’s younger brother George delivered to Johnson his brother’s pledge: if Lyndon wanted to run in 1942, the money would be available again—all that was needed"

"The fact that Lyndon Johnson, who had never directed any industrial enterprise (unless one counts the Texas NYA, whose main function was to provide campus jobs for high school and college students), wanted a comparable job shows how lavish was his appraisal of his own

abilities"

-Massive exaggerations of his 1- flight war service to the point where it bore almost no resemblance to reality- this was picked up by DC.

-War stories told with the vividness of a master story teller.

-The single trip was enough that Johnson considered it "politically essential".

-World War II - and Johnson's success in awarding his constituent corporation a giant federal contract put him on the map and gave him prospects to run for the Senate.

Moses pg. 394

-"..one way not to get things done in New York was to pick a fight with Heart and his 3 newspapers". Moses bribed the publisher with millions - an award covered up in a so-called 'purchase'.

-Moses hired a retired US Army General to control his administrative staff. Mayor La Guardia called him "a prussian and a nazi".

-Moses' road and bridge planning was designed to maximize toll revenues (due to the need to repay gov't bonds) and disregarded driver efficiency.

--

*Relevant to Moses and LBJ: "Sometimes severity is the price to pay for greatness".

Amazing chapter on Moses campaign for Governor of NY:

"In part, it lies in the arrogance that was that nature's most striking manifestation. Robert Moses' arrogance was first of all intellectual; he had consciously compared his mental capacity with other men's and had concluded that its superiority was so great that it was a waste of time for him to discuss, to try to understand or even to listen to their opinions. But there was more to his arrogance than that. Had it been merely a product of a consciously reasoned comparison, it would have been governable by reason, reason that must have informed him that if he hoped to win the prize he so desperately wanted he must for a period of a few weeks conceal his contempt for the public. Had his arrogance been merely intellectual, he could have disciplined himself—this man with a will strong enough to discipline himself to a life of unending toil—for the few weeks necessary to give him a chance at the Governorship. But his arrogance was emotional, visceral, a driving force created by heredity and hardened by living, a force too strong to be tamed by intellect, a force that drove him to do things for which there is no wholly rational explanation. It wasn't just that Robert Moses didn't want to listen to the public. It was that he couldn't listen, couldn't—even for the sake of the power he coveted—try to make people feel that he understood and sympathized with them.

And there was something else behind Robert Moses' arrogance, a strange, flickering shadow. For not only could Robert Moses not help showing his contempt for others, he seemed actually to take pleasure in showing this contempt—a deep, genuine pleasure, a pleasure whose intensity leads to the suspicion that, in a way, he needed to display his superiority, with a need so great that he simply could not dissemble it. How else to explain the fact that, even when he was appearing before the public to ask for its support, he could not help ostentatiously flaunting condescension and boredom—boredom even at its applause? Robert Moses may, moreover, have understood that he had this need. He may have understood that he would not be able to appear before the voters without having to show them —so clearly that there could be no mistake about it—how much he despised them. For such self-knowledge would explain—and it is difficult to find another explanation—his decision to shun, to so perhaps unprecedented an extent, all public appearances save for a few formal speeches.

Such an explanation also helps to illuminate Moses' otherwise almost inexplicable treatment of the press.

Nobody understood the press and how to manipulate it better than he. And therefore he must have known, intellectually, that he would forfeit its support—support he both needed and wanted—if he attacked reporters personally and directly. Something far stronger than intellect, something stronger than considerations of strategy, stronger even than a chance for the Governorship, wadriving him, something that made it simply impossible for him to accept criticism, even the discreetly implied criticism of the reporters' questions at his first press conference.

As for the vilification that he spewed over his opponent and everyone connected with him—former friends as well as enemies—it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the explanation for this, too, lay in character rather than campaign tactics. Since his earliest days in power, Moses had tried not just to defeat but to destroy anyone who stood in his way—by any means possible. The definitive word on Robert Moses' gubernatorial campaign may be an unconsciously revealing remark that Moses made years later to his friendly biographer, Cleveland Rodgers: "I made the only kind of campaign I knew how to make."

Afterwards: FDR tries to eliminate Moses:

"For Moses still possessed a weapon more valuable even than his popularity: his mind. He conceived a masterstroke that simultaneously won him back his popularity and turned the tables on his great enemy. While La Guardia was in Washington, he did the one thing that no one involved in the closed-curtain drama had expected. He leaked the order to the press—and thereby pulled the curtain up.

There, suddenly spotlighted before the public, stood the President of the United States of America—caught in a most unbecoming posture."

**Moses had accumulated so much power and reputation that it was difficult for even the POTUS to fire him.

*Media tactic: ignore the person (negative) for the shared principle (positive)

"Before his gubernatorial campaign, Robert Moses had been a hero because the public had seen him less as an individual than as a symbol of resistance to politicians and bureaucrats. His conduct during the campaign had, by forcing the public to see him as an individual, stripped him of that cause. But now he was once again basking in its aura—and he was once again a hero. In a display of indignation that proved how completely the Moses masterstroke had restored its author to public favor"

"The Mayor was frantically steering between the Scylla of losing federal

funds and the Charybdis of losing the confidence of his constituency. And he had to steer small indeed."

LBJ pg. 607

-LBJ concealed the fact that he was FDR's man in Roosevelt-Garner fight. The Republicans did not even know that he was their mortal enemy. He avoided speeches for a year and avoided being in Texas. Sneaky, Low profile, as much as possible... was LBJ's way.

-The massive contracts won by LBJ for Brown & Root had little to do with B & R's expertise and entirely to do with winning the political process. B & R simply funneled federal funds into sub-contractors.

-Corporations that wanted to expand their operations and profits knew that the main way to do so was through federal funds from Washington. Influence at the national gov't..

-Lady Bird longed to buy a house circa 1941 but they didn't have enough. The millions of corporate money was entirely funneled to get LBJ elected.

". And whereas before the war, Johnson had been a dynamic and effective Congressman in improving the lives of his constituents through rural electrification and other public-works projects, wartime shortages of materials now brought

such projects to a virtual halt. Work for the Tenth District was largely limited to servicing the requests of individual constituents, and for the duration of the war, increasingly this work was carried on not by Lyndon Johnson but by his staff. His political acumen and energy were, for the duration, no longer used for politics. They were used for making money"

"During the war, Lyndon Johnson grabbed for money as eagerly as he had grabbed for political power. Inexperienced in business, he displayed, for some years at least, little business expertise or instincts. But he didn’t need any. For the basis of his business enterprise was not business but politics. His first step, in fact, was a case study in the use of political influence to amass wealth."

Moses and manipulating the Mayor and the NYC media, including the majority owner of the New York Times pg. 467

-Mayor La Guardia's tactic was to make ostentatious displays to show that he was firmly in charge. He manufactured an impression that there was no part of the city in which he did not dominate. However, it was a cover-up...and empty in the case of Moses and elsewhere.

""He boasted to newspapers [of] his appointees. ... He did not say that he often treated his commissioners like dogs. . . . We soon discovered that we were expected to do a good deal of humiliating kowtowing, to give many of La Guardia's favorites jobs, and to respect without question whatever capricious notions the Mayor might have about our work.""

""Temperament? There's no time for it—unless it happens to serve a useful purpose."

"The aide who was perhaps present most often was Reuben A. Lazarus, whose expertise in bill drafting, second only to Moses', had earned him the nickname "the walking library" and a reputation for knowing "where the bodies are buried" and who was considered so indispensable that La Guardia had retained him in the same sensitive post in which he had served Jimmy Walker—official city representative in Albany—and had given

him extraordinary access to his private office"

"In a way, their vicious confrontations made La Guardia respect and admire Moses. The Mayor's intimates noticed that while he liked to push people around, he only respected those he couldn't push. "I think he put on a great deal of his brutalities to test people out," C. C. Burlingham observed. "If they could stand up against him it was all right, but if they couldn't they were in bad luck.""

"And because accomplishment was desperately important to both men, while their disagreements may have been made fierce by personal characteristics—their blazing tempers, their arrogance, their dogmatism and their insistence on having their own way—the roots of those disagreements lay not in personal hostilities so much as in differences of opinion about what should be accomplished and how, and therefore their disagreements could always be resolved. So intensely interested were both men in their work, moreover, that often no resolutic n was necessary. "You'd see the two of them in the goddamnedest argument and then five hours later they could go and have a drink together

and you'd never know they had fought," "

"His dreams for the beautification were vast but vague, and no one appreciated better than he the enormous difficulty in filling in the vague outline of a magnificent metropolis with specific plans and then in obtaining the money—the chisel and the brush—that would allow him to turn the plans into reality. "

And it was Moses who was enabling him to obtain the plans and the money.

"by 1936, New York City was receiving one-seventh of the WPA allotment for the entire country—and the Mayor knew who was responsible. He must have known every time he went down to Washington for one of the frequent mayors' conferences called by the WPA. There would be hundreds of mayors there"

"but when they were confronted with the blunt questions of the Army engineers WPA chief Harry Hopkins had brought in to screen proposed projects, they had to confess that the blueprints weren't ready, or the specifications weren't ready, or the topographical surveys weren't ready. La Guardia watched many of them walk out of the conferences humiliated and without the money they were asking for. But he had blueprints. He had specifications. He had topographical surveys. He had every piece of paper that even the hardest-eyed Army engineer could desire. And he had them because of Moses. "

"And Moses, the skillful manipulator of men, found plenty in La Guardia to manipulate.

There was, for example, the Mayor's boundless enthusiasm for engineering and engineers.

Moses played on this feeling. He was constantly pressing La Guardia to accompany him on inspection tours of construction sites"

-Sense of drama, gift for words- Moses worked to make the La guardia giddy with his presentations, tours, and displays. He gave La Guardia a ringside seat.

""This is the most thrilling moment I have had since I became mayor. ... I congratulate the Authority, the engineers, the contractors and every man who has had a part in this magnificent piece of work. Moments like this make up for many heartaches and disappointments." "

"He wanted Moses' admiration. He was jealous of the only man who really had it. Moses recalls that "when the Mayor was mad at me, which was not infrequent, he would say, 'The only boss you ever had whom you really respected was Al Smith. What's he got that I don't have?' " (Moses recalls that "I always answered that I admired both of them, but thought Smith a better executive" because he always stood behind his subordinates.)"

"Moses played on this predilection. He gave the Major pageantry such as no mayor had ever enjoyed in democratic America"

"Already predisposed to be friendly toward Moses because he was creator and defender of parks, the city's thirteen daily newspapers had that friendship cultivated with customary Moses thoroughness.

As always, he went directly to the top, giving newspaper owners pre-opening tours of new bridges and free passes to them thereafter, inviting them to sail on the Long Island Park Commission's yacht, bathe in the reserved section of Jones Beach and dine in the private section of the Marine Dining Room—where he served them lavish helpings of his inimitable charm; He spent many weekends at their summer homes.

Moses also lavished attention on top editors. He had easy access to the Herald Tribune's because his Yale classmate Harold Phelps Stokes was one of them, and he used that access.."

"Moses would be waiting in the lobby [of Merz's apartment house] many mornings to ask him if he wanted a lift downtown—so he could plant an editorial."

And while Moses went to the top, he did not stop there, wining and dining reporters as well as publishers, inviting key ones to his elaborate opening-ceremony luncheons, to an annual swimming and dinner outing at Jones Beach, to more intimate, and elaborate, luncheons at Belmont Lake State Park, to the Park Department's Christmas party at the Arsenal and to day-long yacht trips, which often ended with clam and lobster bakes on Fire Island. At all these events the food was superb, the liquor flowed freely and so did the charm.

The most important newspaper in the city—and in the country—was The New York Times, and Moses had an especially strong hold over the Times: the devotion to parks of the woman who owned approximately two-thirds of its voting stock"

" His usual technique with Mrs. Sulzberger was not to walk away but to walk with—to take her himself, or have Madigan or Andrews take her—on a tour of the area in dispute to try to sell her on his idea of how it should be developed. These walks were planned with care..

And the walks usually worked— particularly since Moses' opponents did not know her well enough to take her on walks themselves and show her their side of the argument and did not have the facilities or manpower to compile the facts and figures that might have disproved Moses' facts and figures. Moses persuaded Mrs. Sulzberger to persuade the Park Association to elect Andrews, a native Virginian who could be as courtly with women as he could be curt with men (Mrs. Sulzberger says he was "a remarkable man"), to its board of directors, and thereafter there was someone working for association support of his policies from within."

"." The letter even closed with a threat. "This particular question does not seem to me to be important enough to quarrel about, unless you insist on proving your generalizations, in which case I am prepared to refute them by a public exhibition of plans, photographs, maps and supporting figures."

"Mrs. Sulzberger's influence on the newspaper of which her father had been, and her husband was, publisher was not overt. Intrusiveness was not her style, which was so reasonable, dignified and soft-spoken that people sometimes mistook her gentleness for timidity. But, as the Times's historian, Gay Talese, has pointed out, "no perceptive editor . . . made this mistake." "Her most casual remark," wrote Turner Catledge, later managing editor, "would be treated as a command."

"Moses' press releases were treated with respect,being given prominent treatment and often being printed in full. There was no investigating of the "facts" presented in those press releases, no attempt at detailed analysis of his theories of recreation and transportation, no probing of the assumptions on which the city was building and maintaining recreational facilities and roads. The Times ran more than one hundred editorials on Moses and his programs during the twelve-year La Guardia administration—overwhelmingly favorable editorials"

. "He didn't want to fight with Moses no matter what." Lazarus says. As long as he didn't fight, La Guardia had learned, Moses would provide him with a seemingly inexhaustible cornucopia of political benefits. If he did fight, Moses would humiliate and defeat him. The little Mayor had learned—the hard way—that it was better not to interfere.

"Moses' ability to complete public works fast enough to provide a record of accomplishment for an elected official to run on in the next election; his ability to build public works without scandal; his willingness to serve as a lightning rod to draw off opposition from the elected official—most of all, perhaps, his matchless knowledge of government. "

" Says Judge Jacob Lutsky, who not only served in the La Guardia administration but was a top adviser to Mayors O'Dwyer, Impellitteri and Wagner: "You've got to understand—every morning when a mayor comes to work, there are a hundred problems that must be solved. And a lot of them are so big and complex that they just don't seem susceptible to solution. And when he asks guys for solutions, what happens? Most of them can't give him any. And those that do come up with solutions, the solutions are unrealistic or impractical—or just plain stupid. And those that do make sense—there's no money to finance them. you give a problem to Moses and overnight he's back in front of you—with a solution, all worked out down to the last detail, drafts of speeches you can give to explain it to the public, drafts of press releases for the newspapers, drafts of the state laws you'll need to get passed, advice as to who should introduce the bills in the Legislature and what committees they should go to, drafts of any City Council and Board of Estimate resolutions you'll need; if there are constitutional questions involved, a list of the relevant precedents—and a complete method of financing it all spelled out. "

"He had solutions when no one else had solutions. A mayor needs a Robert Moses."

" Not the city but the federal government was paying for the bulk of those public works, and the federal government was much more interested in speed, in getting something to show for its expenditure, than in the considerations that would at least partially motivate a mayor— priorities, location and design, for example. And, because speed of construction depended upon the existence of detailed plans, the federal authorities were therefore primarily interested in such plans. Because the Mayor needed plans and needed them fast, he had no choice but to give priority not to those projects which were most urgently needed, but to those projects for which plans were available—and to a considerable extent not he but Robert Moses decided which projects those would be. Because not he but Moses had the "large, stable planning force" of engineers trained to design urban public works on the new, huge scale made necessary by the growth of the city and made financially feasible by the new federal involvement, to a considerable extent he could not even evaluate those plans. He could not argue intelligently for changes in the location or the design Moses was proposing."

LBJ pg. 676: Most campaign contributors do not give their money early enough and in large enough quantities to receive maximum return on investment; thus they have limited effect on favoritism in the awarding of gov't contracts, the gifting of corporate/personal ambassadorships, and in manipulating the details of policy.

-in legislative bodies, personal relationships are so important that any shift causes a re-arrangement.

-power of money is less ephemeral than the power based on elections and individuals.

-LBJ's duty was also to help his campaign contributors maximize their own profits for gov't contracts awarded.

-LBJ's oil connections wanted favorable profit accounting, tax benefits, exemption from federal regulation, new exemptions and gov't favoritism.

-LBJ: the prince of flattery- by increasing the importance of the person he is talking to.

-LBJ "touched every base" and this giant quantity of work paid dividends: He got connections in the white House. LBJ cultivated not only bureaucrats, but their secretaries and their assistants, and their assistants' assistants! He used shared love for FDR to cultivate these relationships. He gave important ones favors and kindness.

"And then, in 1942, Ulmer made a fatal misstep: he decided to retain an attorney who was known to have influence with government agencies, and the attorney he chose was Alvin Wirtz"

"He knew Lyndon could persuade them, he was to say with a smile; convincing liberals that he was a liberal, conservatives that he was a conservative, “that was his leadership, that was his knack.”"

Moses pg.470:

-After New York public money was tapped out, Moses directed his energy towards taking public money from the federal government.

-An improving economy was a negative for Moses- less Keynesian spending and funds allocated from the gov't.

- "His usual technique with an insufficiently compliant departmental official was to demand that he be fired." * I have seen this before- people do this when they can get away with it with no negative effects on their own reputation.

-Moses hired a group of people whose only purpose was to reveal damaging personal information on his enemies and people he wanted to fire. If they couldn't dig up any, Moses invented it and spread false rumors.

-The next step was to refuse to deal with the official involved or allow any of his aides to deal with them. This was a threat that ceased activity and forced the other party to surrender and act.

-Moses next step towards his non-compliance was to use his high standing among the public as a genius and great public servant to attack the enemy via the media. The masses have such regard that immediately his opinion holds weight.

* Warren Buffet enjoys similar powers.

-Famous men with established reputations are less vulnerable to these attacks, but unknown men with budding reputations can be severely damaged.

-Vague attacks/generalizations have the effect of conjuring up unpleasant notions in the brains of the recipients and have the advantage of being difficult to disprove; thus less vulnerable to lawsuit/libel.

Moses pg. 500

" 'Goddammit, I got my office organized in forty-eight hours. If you fellows don't get going, I'm going to call up the press and tell them what a bunch of incompetents you are.'"

The lesson wasn't lost on Chanler. "If you stood right up to him, he backed right down," he says. "He was just a natural bully. So whenever he tried something, I'd pretend to lose my temper. And after a while, he didn't try any more."

"But the other commissioners didn't know Moses as well as Windels and they didn't have the benefit of his advice—and when Moses' harsh voice rasped over the telephone into their offices threatening to take them to the press and the Mayor, they thought the only way to avoid such a fate was to do what he wanted. Many of the other commissioners despised and resented Moses. When they attempted to establish an esprit by meeting for weekly "commissioners' luncheons," Moses refused to attend—a gesture that they interpreted, correctly, as an attempt by Moses to show them that he considered himself above them.

They considered the plant from a Park Department greenhouse that Moses sent in his place each week a gratuitous insult. But while they might despise and resent Moses, they also feared him.

And they generally did what he wanted. Even the more independent among them, moreover, were outwitted by his brilliance in the bureaucratic arts"

"Pointing out to a recalcitrant commissioner that because of the Park Department's unprecedented activity, its demands on the commissioner's own department were undoubtedly disrupting its normal procedures, Moses would suggest that the commissioner designate one of his aides to do nothing but handle Park Department liaison, perhaps even allowing him to work in the Arsenal. Then Moses, by bullying or by charm, would take the aide into camp—making him an ally of the Park Department and thereby practically freeing himself of the necessity of winning the other department's approval of his actions. Soon Moses had his "own man" in the office of many other commissioners—men loyal to him rather than to their own commissioners and useful to Moses not only as liaison with other departments but as spies within their ranks."

"He drove wedges, too. In his 1935 budget request, he asked the Board to allocate $3,600,000 for construction projects in Jacob Riis, Fort Tryon, Pelham Bay and the two Marine parks. The Board did, and the thin edge of the wedge was in. Year after year, thereafter, he returned to the Board for new allocations which he said were necessary to make the improvements built with the previous allocations "usable"; unless the money was given, he would say, the previous allocations would be wasted."

"He deceived the Board constantly. To obtain permission to construct a stadium on Randall's Island, he had assured the Board that the "PWA" project would cost the city "not a penny." Then, with permission obtained and work under way, he announced that he would need ..."

"but because the Board had left itself open to political blackmail by approving earlier fund requests without adequately checking them, it was helpless to deny him later requests and thereby allow him to charge that it had wasted the public's money by building only part of a project. Moreover, since the Board's membership was continually changing, just as one borough president or Comptroller learned never tc trust Moses' figures, he would lose an election and the man who took over his seat would have to begin the learning process anew. And, most important, while the Board may have distrusted Moses' figures, its lack of adequate engineering assistance prevented it from coming up with any of its own."

"Those on the Board who tried to bring him to heel soon wished they hadn't. When they dueled with him, they did so from the dignity of then-seats behind the massive raised mahogany horseshoe in the Board chamber, backed by fluted Corinthian columns and wine-red draperies. But their setting couldn't save them from his tongue.

"He would enter the chamber hearty, very hearty, with this broad grin," recalls McGoldrick, who, as Comptroller, sat in one of the seats on the horseshoe. "He was very impressive, tall, handsome, and he'd always come in with a team of his aides behind him—a different team for each project. And he knew his stuff inside and out. He wasn't like [some of] the other commissioners, who had aides with them and every time you asked them a question, they had to turn to them and whisper to get the answer. And this was very impressive. His men didn't seem to have any purpose there, except that one or two always stood behind him to hand him papers when he needed them. When the matter in which he was interested was called he would walk to the railing at which officials stood to address the Board—there was no public-address system or microphone then—with the same grin. He was very breezy and self-confident. I remember his coming up very genially, with his head thrown back and a grin on his face."

But let one of the Board members venture to criticize—or even to question—one of his projects, and the grin could fade in an instant. "[He was] very intolerant of any criticism of anything he wanted to do," McGoldrick recalls. "He wanted to do it. He was going to do it. And withering with his adjectives anyone who opposed him." Says one observer: "When someone else was speaking, he'd begin to pace up and down. He'd turn his back—total boredom. Off to one side a little. Then he'd suddenly whip around without asking permission, walk up and make some sharp remark . . . often out of the side of his mouth, you know, throwing his shoulders around. There was no indication of respect—he seemed to emanate an air of arrogance, of contempt, for the men sitting up there." If he felt called upon to make extended reply, he would do so while rocking slightly on his heels, his large head thrown back and to one side, and the words that rasped out of the handsome, sensual mouth were devastating. "Time and again," said one magazine writer, "he transfixes his opponent with graceful malice."

As for the Board of Aldermen and its successor under the new Charter, the City Council—he treated those worthies, many of whom he told Lazarus he could buy "with a couple of jobs," like men who could be bought with a couple of jobs. Or he simply ignored them. In 1939, he urged the Park Department's 3,000 employees to vote against councilmen who had slashed the Department's budget requests, and when the Council, after hearing a committee report calling Moses' action "one of the most brazen attempts at political intimidation in the history of the city," ordered him to appear before it to explain the action, he simply didn't bother to show up, sending a letter saying he hadn't received "adequate notice."

"Bob Moses has climbed so high on his own ego, has become so hidebound in his own arbitrariness, that he has removed himself almost entirely from reality and has insulated himself within his own individuality

This difficulty could to some degree have been overcome by sheer mental ability. Robert Moses' mind was supple, resourceful. Even without input of social and human considerations, it could have deduced some of these considerations simply by thinking about the problems involved.

But Robert Moses no longer had much time to think.

Building a state park system had been an immense job, but he had brought to it not only immense energy but immense ability to discipline that energy.

"When there is no time for the thinking required for original creation, the tendency is to repeat what has proven successful in the past. "

Moses pg. 504

-Work habits: 14 hour work day, minimum, 7 days a week. No vacations taken.

"Power is being able to ruin people, to ruin their careers and their reputations and their personal relationships. Moses had this power, and he seemed to use it even when there was no need to, going out of his way to use it, so that it is difficult to escape the conclusion that he enjoyed using it.

He may have felt it was necessary to turn the power of his vituperation on men whom he felt posed a threat to his dreams, but he turned it also on individuals who posed no such threat"

"he had to attempt to damage their reputations beyond repair by charging— falsely—"

A streak of maliciousness and spitefulness seemed to run through Moses' character, and he gave that full play, too"

"Anticipating that the matter would become public knowledge, Moses went to the press—and he did so with his usual blend of demagoguery and deception: breaking the story himself to get his side of it before the public first; oversimplifying the basic issue to one of public vs. private interest; identifying the "private interests" with the sinister forces of "influence" and "privilege"; concealing any facts that might damage his own image. "The whole question," he said, "is whether public interest is going to yield to private,"

"Moses' methods "did intimidate people from debating with him. And it intimidated us, too, most likely.""

" And he bolstered his arguments with floods of facts and figures compiled by his corps of statisticians. The facts and figures were misleading, but no one did the work necessary to disprove them"

LBJ

"But his political influence had everything to do with many of the advertisers who bought time on KTBC.

The backers who had arranged for money to be contributed to his political campaigns now arranged for money to be contributed to his radio station. Herman Brown gave him some advertisers.

Ed Clark was coming to be known, as Alvin Wirtz was already known, as a lawyer to go to in Austin if you wanted something from the federal government. Clark, a power in his own right, had never been intimidated by Johnson;

he was too independent to take orders from any politician—and too astute What Johnson wanted was

advertising revenues; what Clark wanted was recognition as a lawyer with influence in Washington—and both got what they wanted.

As one businessman puts it: “Everybody knew that a good way to get Lyndon to help you with government contracts was to advertise over his radio station.”

Although they were ostensibly buying airtime, what they were really buying was political influence. They were buying—and Lyndon Johnson was selling"

"IN RECRUITING A STAFF for KTBC, Johnson was using the same methods he had used in recruiting his political staff. There were, in Austin as in Washington, the charm and the promises deployed to persuade a man to leave his job and go to work for him"

"ring the first six months of the Johnson ownership, the Congressman himself did not come to Austin often, but when he did, Weedin would bring up the subject and the

Congressman would stall. “Lyndon would never give me a contract because he could never decide if the ten percent was before or after taxes,” Weedin says. "

There was a more serious, if less tangible, source of tension between the two men. During the 1941 campaign, Weedin had become a fervent admirer of Lyndon Johnson. “He must have sold me, or somebody sold me, or I sold myself on doing whatever I could to get him elected. So I became a thorough Lyndon Johnson follower.”

Weedin’s attitude toward Johnson was that of a younger man toward an older man who is his hero.

Attempting to define it, Weedin says, “The minute he walked in, he’d take over the room.… He had a

tremendously commanding presence, and as everyone says, the one-on-one things, he was fantastic.” He speaks of Johnson’s “domination.… He never let up on that at all. He was a completely overwhelming man in person.” And, he says, Johnson “intimidated” him: “He was the only person who could ever make me nervous.” During their discussions about the station, “he would grill me.”

Whenever he would come in, I would be so up on things that I wanted to tell him that were going on, I’d done so much homework on everything to report to him, that I was a bundle of [nerves]. And I’m not a nervous man, but I was a bundle of nerves going in to talk to him.

No matter how admiring, respectful and intimidated Weedin was by Lyndon Johnson, he couldn’t be as admiring, respectful and intimidated as Johnson wanted him to be. Other employees of KTBC saw this. John Hicks recalls: “He wanted Harf to be a slave, and Harf just wasn’t like that. He was young and eager, but he had a kind of dignity about him. He just couldn’t be what Johnson wanted.” He was very bright—and he

did know the questions Johnson was about to ask. And that was too bright for Lyndon Johnson.

“I think he had a gift for getting from people whatever he wanted,” Mrs. Robinson felt. “I remember thinking that the Three E’s of manipulation are ‘ensnare,’ ‘enthrall’ and ‘enslave.’ And he was adept at any one of the three.” Among themselves, some staff members talked of the dangers of becoming “enslaved”

by Lyndon Johnson, who, they felt, tried to “get someone so obligated that they couldn’t [leave his employ].… He would bestow favors, to make it so worthwhile to be attached.” Once you accepted a favor, “there was a large amount of gratitude” that made it harder to leave.

And, Hicks recalls, that was all Johnson said: “It was like a curtain came down.” The Congressman turned and left. So far as Hicks remembers, Johnson never spoke to him again.

GRADUALLY, Lyndon Johnson put together the kind of staff he wanted—composed of men who had demonstrated an unusual willingness to allow him to dictate their lives

"But some of the considerations that tied Kellam to Johnson may have been more subtle than economic ones. Men who had observed the relationship between the two men had watched a powerful personality becoming steadily submerged in one much more powerful, until little trace of the first

" it was not the brilliant, energetic but independent Luther E. Jones (later to be known as the “finest appellate lawyer” in Texas) whom Johnson selected to be a permanent member of his team but the other assistant, the more malleable, if

considerably less talented, Eugene Latimer. remained."

"The hunger that gnawed at him most deeply was a hunger not for riches but for power in its most naked form; to bend others to his will. At every stage of his life, this hunger was evident: what he always sought was not merely power but the acknowledgment by others—the deferential,

face-to-face, subservient acknowledgment—that he possessed it. “You had to ask. He insisted on it.”

It had been evident in the men with whom he surrounded himself, in the way he treated them, in his unceasing efforts, even as a junior Congressman, to dominate other congressmen, to dominate every room in which he was present "

Says Clark: “He wanted people to kiss his ass. He didn’t want to have to kiss people’s asses. And selling [radio] time—you have to kiss people’s asses sometimes. In business you have to. He liked power, and so he was unhappy in business.”

Politics, and only politics, could give him what he wanted.

*Power resides where men believe it resides".

LBJ- Book 2

- On referring to the Senate vs. State Governorship: "The Texas governorship was a possibility, and indeed in 1946 there would be speculation that Johnson would run for the governorship, but on Johnson’s road map, the governorship—or any other state post—would be only a detour, a detour that might turn into a dead end. State office had no interest for him, he reiterated

whenever the subject was brought up; years later, when John Connally was leaving Washington to run for Governor of Texas, Johnson would ask him, “What the hell do you want to be Governor for? Here’s where the power is.”"

"As for appointive office, as he often explained to supporters, “You have to be your own man”—his own man, not someone else’s; an elected official whose position had been

conferred on him by voters, not by a single individual—who could, on a whim, take the position away. The ladder to his great dream had only three rungs, and appointive office was not one of them."

Truman’s daughter,

Margaret, says that because her father had witnessed the professional son in action with Rayburn, “he never quite trusted him

"The situation grew still more discouraging. Johnson’s chief remaining ally in the Administration’s higher reaches was Secretary of the Interior Ickes"

"Tommy Corcoran, once so influential with the White House, was so thoroughly disliked and distrusted by Truman that the President had ordered his telephone tapped. Johnson sought for chinks in the wall around the new President; when Truman’s mother died in Grandview, Missouri, Johnson wrote him that he was donating a book in memory of the “first Mother of the Land” to the Grandview Public Library."

"Johnson worked assiduously at cultivating two younger members of the Truman team"

Moreover, with the waning of the Roosevelt influence, conservatives had consolidated their political power in Texas. If Johnson was ever to run for the Senate, he needed their support, and needed to erase from their minds the impression that he was a New Dealer.

The Speaker did what he could for him. Appointments to two prestigious new committees were in Rayburn’s power, and he appointed Johnson to both the House and Senate Joint Committee

his attempts to carve out a prominent role for himself on these committees resulted merely in resentment from the other, more senior, members.

During his first eleven years in Congress, he delivered a total of ten speeches—less than one a year. He refused also to fight in the press on national issues.

He refused to fight not only in public but in private. Helen Gahagan Douglas was a congresswoman herself now, and her earlier impression of Johnson’s constant awareness “that what he said might be repeated or remembered—even years later” was confirmed. She noticed that at dinner parties Johnson still talked a lot—but he still seemed never to say anything substantive. She felt she understood those tactics. Lyndon Johnson, Mrs. Douglas

says, was looking down a “very long road.”

But he was making no progress along it. Instead, there were continual reminders that he was slipping back.

" He no longer possessed any power of his own, and since he could not resist trying to dominate other men, he was

constantly being reminded of this. His attempts to act toward his fellow congressmen as he had acted when he had possessed at least a modicum of independent power—the power of giving them campaign contributions or, because of his White House access, administrative favors—aroused only resentment. "

" “Johnson kept asking for favors, and he simply didn’t have that many to give in return.” He tried too hard—much too hard—to trade on what minor “help” he had given. “You can do those things once or twice,” Van Zandt says. “He did them too frequently. People would get irritated."

"He was rebuffed even in an attempt to assert his power over one of his committee’s young staff members. Thirty-year-old Bryce N. Harlow did not, in Johnson’s opinion, show him sufficient subservience, so in 1947, the Congressman attempted, Harlow says, “to take me to the Johnson School.”"

“Lyndon would maneuver people into positions of dependency and vulnerability so he could do what he wanted [with them],”

"Once, he asked Ed Clark the reason that he was not more “loved” in the district for which he had done so much. “That’s simple,” Clark said, with his customary candor. “You got rich in office.” "

" if his 1941 campaign had brought him recognition across the entire state, the intervening seven years had largely erased it: his name was little known to the electorate outside his own district. And he

wouldn’t have Roosevelt’s name behind him this time. His chances of winning a 1948 election were not good"

-The anti-New Deal oilmen didn't care about Johnson's liberal politics- as long as his election would protect their profits. So they contributed.

LBJ book 1, until end.

-LBJ paid media outlets to convert his press releases into news stories..for cash. These negotiations were done with the help of PR specialists. However, the content of the propaganda had to be acceptable to the news runners.

-not all newspapers/media could be influenced by money.

-LBJ's lower personal performance in the failed 1941 Senate campaign: 1. Colder, more mechanical rather than warm and social (meeting and greeting the public) 2. lost a lot of his desperation/energy due to complacency. Not working as hard. Confident of victory due his superior finances and campaign organization 3. excessively authoritarian/alienating/condescending/monotone speaking style with speeches that were too long. It made him look too alien, and not "one of us". 4. physical style: too elitist, rather than ordinary in 1937. 5. LBJ aged 10 years in 3 due to stress; also gained weight.

-FDR had no sympathy for losing D- politicians and usually cut them off from contact. Not Johnson though.

-Restoration of the Rayburn-LBJ relationship: "the coldness of a father towards an estranged son melts as soon as the son is in danger".

-Lady Bird's graciousness and elegance towards Rayburn was always crucial- House speaker Rayburn was back with his surrogate family.

-The power of Rayburn was that of survival; he never rose beyond Speaker but unlike ephemeral officeholders.. he was there to help with his powerful resources. LBJ devoted optimal energy and skill at keeping Rayburn with him.

-However, the 'blind love', due to the betrayal, was forever gone. LBJ was pushed down a notch and Rayburn expected deferential treatment towards him, even when LBJ became Senate Majority Leader. What Rayburn demanded, LBJ gave.

* a struggle in office politics is to avoid the loss of standing; it must be continuously replenished, and not backed down from a certain level.

Caro's chronology of Moses' character change throughout his lifetime:

Naive idealist --- > Failed Reformer ----> learning to become a practical operator with its loss of ideals -- > becoming the ruthless and cruel master practitioner

The other parts, not read yet:

-Increasing signs of brutality, corruption, and greed- at this center of this is extremely acute forms of arrogance, build up steadily by countless victories.

5. The Love of Power 6. The Lust for Power 7. The Loss of Power

LBJ- Book 2, Means of Ascent

Governor-General Coke Stevenson was one of the best lawyers in Texas. Reading habits (Morning and night, 4AM).

" He had been elected to office by his fellow Hill Country ranchers, by his fellow legislators—by people who knew him, and who knew the depths concealed by silence and a poker face. "

" Underlying everything was that Coke Stevenson was not a politician as anyone would define a politician. He was not a social person. The dinner party, the cocktail hour, the niceties of a reception—he just didn’t like that. Coke Stevenson couldn’t

work a crowd. He wasn’t a backslapper. He couldn’t do the ‘Hi, there! Sure good to see you! Lookin’ for your vote Saturday!’ He didn’t have the perpetual grin showing his teeth all of the time. Campaigning did not come easy for him. For him to go into a town and walk the streets …”"

"He was just as adamant about other—more traditional—political apparatus. He refused to issue a platform, or to make campaign promises. A platform, he said in his dry way, was like a Mother Hubbard dress: it covered everything and touched nothing. Platforms and campaign promises were meaningless; politicians issued them or made them, and then as soon as they were elected forgot them. They were phony, he said, and he wasn’t going to have anything to

do with them. Voters could know what he was going to do, he said; all they had to do was look at what he had done. He wasn’t going to change"

" “The trouble with him,” one state Senator said, “is that he insists on

talking to a man’s intellect, not his prejudices.”"

" He made these gains with a very subdued style of governing. He governed not by dramatic special messages or by the noisy, unproductive confrontations with the Legislature that had characterized state government or years, but by conferences with individual legislators and state officials. Arriving in his office, they would find that their proposed bills or budgets had been blue-penciled—

Stevenson kept a supply of blue pencils on his desk for that purpose—and they found also that the man who had done the editing knew at least as much about their departments as they did, so that his arguments for reduced spending were hard to resist. The confrontations ceased, as abruptly as if a strong hand had turned off a spigot, and so did the incessant, argumentative and costly special sessions of the Legislature. Somehow, without confrontation or drama, the economies that Stevenson wanted so badly to bring to government took hold, without reductions (and in many areas, with increases) in the level of governmental services.

When liberals later criticized him for having had “no program,” Stevenson would reply, “Well, that’s not exactly right. I had a program. It was economy.” Within that definition, he was very successful. "

* Instead of allowing group battles, he negotiated compromises individually and matched them.

Moses pg. 577

"What lay between the two young reformers and Moses was partly a question of values.

Moses' had been formed in a different age, the age, twenty years and more in the past, when he had been a young reformer. To understand his dream for the West Side Improvement, one had to understand the age in which he had dreamed it"

" only the bankers' ideas mattered because it was the bankers who had to put up the money for the bridge. Moses could not, in fact, allow any discussion of the bridge location at all, because discussion generates controversy, and controversy frightens away the timid, and no one is more timid than a banker where his money is concerned. "The market was so skittish that any little thing could have gotten them to back out," Jack Madigan recalls. "A lesser fellow wouldn't have understood the importance of killing off this agitation right at the start before it began raising up some publicity and getting people arguing," but Moses understood perfectly. The financing of the northern section of the West Side Improvement had been made possible only by remarkable ingenuity on Moses' part, an ingenuity that bent rules and regulations—twisted them, in fact, until they were all but unrecognizable—into a shape that permitted the participation in the financing of the project of bankers and twenty-two separate city, state and federal agencies. Exposure of that ingenuity to the public would tumble in an instant the house of cards he had so laboriously erected. He could not allow it"

"The media, whose amplification of his statements without analysis or correction played so vital a role in making the public susceptible to the blandishments of his policies, carried out the same effective if unintentional propaganda for his personality"

"feature stories or long interviews, it said he was totally honest and incorruptible, tireless in working sixteen- and eighteen-hour days for the public, and it allowed him to repeat or repeated itself the myths with which he had surrounded himself—that he was absolutely free of personal ambition or any desire for money or power, that he was motivated solely by the desire to serve the public, that, despite unavoidable daily contact with politicians, he kept himself free from any contamination by the principles of politics. His flaws reporters and editorialists made into virtues: his vituperation and personal attacks on anyone who dared to oppose him were "outspokenness"; his refusal to obey the rules and regulations of the WPA or laws he had sworn to uphold was "independence" and a refusal to let the public interest be hampered by "red tape" and "bureaucrats"; his disregard of the rights of individuals or groups who stood in the way of completion of his projects was refusal to let anything stand in the way of accomplishment for the public interest. If he insisted that he knew best what that interest was, they assured the public that was indeed the case. If there were larger, disturbing implications in these flaws—they implied that he was above the law, that the end justifies the means, and that only he should determine the end"

"he came to hate Roosevelt, with a hatred so unreasoning and blind that it was all too easy for him to hate the things Roosevelt stood for"

"The old Governor knew he was still an immensely popular figure among New Yorkers."

"But he was afraid that popularity no longer meant respect."

"But a family's devotion was no substitute for the roar of a cheering crowd or for a late afternoon in the Executive Chamber, with a dozen associates helping him veto bills or waiting to see what the Republican legislative leaders up on the Third Floor were going to come up with so that he could draft the strategy that would confound them. He was a natural genius in the art of leading multitudes of men toward great goals"

""That's a slender reed to lean on, Bob," Alfred E. Smith said. "A slender reed."

"He meant that it could break at any time, that you could lose the public support," Emily explains. ""

"Robert Moses was arrogant, equipped not only with the "Moses charm" but with a spigot that could turn off charm at the mere hint of disagreement. So was his brother. Each of the two Moses boys was totally convinced that he was intellectually superior to others, each was totally contemptuous of the products of others' intelligence. From his youth, Robert Moses seemed driven, moreover, by some need—some compulsion, almost—to demonstrate this contempt to those for whom he held it. "

""[Paul] was opinionated—my God! When someone disagreed with him, you have no idea! He could argue you right back against the wall. And just as often he couldn't even be bothered arguing. There was this disregard of someone else's point of view, this brushing aside."

Moses pg. 609

"Not only Robert but Paul was to reveal throughout his life a feeling that the laws that governed other men were not meant to govern him. The drive to dominate, to relate to others from a commanding position, was strong in both"

"Robert's concept of help was that of the mother he imitated, the patronizing "Lady Bountiful" who never forgot that the lower classes were lower. It was the concept of rigid class distinction and separation that would later be set in concrete by Robert Moses' public works. "

" About this woman whom he saw almost every day of his boyhood, he knew nothing more—not even whether or not she was married. "

is brother, Paul Moses felt, had lied about him when he was not around to defend himself, had poisoned his mother's mind and the minds of other members of his family against him, had exaggerated the details of his divorce and his financial difficulties until they seemed like vicious, unforgivable misdeeds.

It was, Mrs. Fink said, "as if he had tried to deny his father, his mother, and his whole youth.

"At the time, she was twenty-four and he was sixty-five, but, she says, "after I had spent the evening with him I was in love with him." "It crossed all generational lines—that charm of his," Joan Cooney says. "What he has is this fantastic recall. He'd tell me what he thought of Tom Dewey and FDR ... He has that ability to tell you a story so you can just see the people in the room . . . And he's just got that magnetism."

"He must have been a wonderful lover. He's so direct. No underlying doubts . . ."

* Caro states: Moses initially sought power to realize his dreams. The seeking had been solely on behalf of the vision. The monumental ends were achieved with the billions of $ expended.

But Moses became addicted to power. For the first time, (1936) he sought power for power's own sake, as an end in and for itself.

***True for much of life's pursuits.

LBJ, book 2- Means of Ascent

"But behind Stevenson’s refusal to repudiate the AFL endorsement lay also Lyndon Johnson’s genius at “reading” men. Johnson had read Coke Stevenson now, and he knew his weakness: his fierce pride, particularly a pride in his reputation for honesty and truthfulness. All his public life—from the time he had been a young county attorney and opponents had attacked his handling of the rustling case involving the son of the prominent Kimble

County family—he had refused to utter a single word of reply to personal attacks. So Johnson, to keep him from replying, made the attacks personal."

"the demands were deliberately couched in language that, Murphey says, “anyone who knew Governor Stevenson knew he would never reply to.”"

*personal attacks

"Stevenson’s response was based not only on philosophy but on the buttressing of that philosophy by a lifetime’s experience. Time and time again during his long career, candidates had attacked him personally and he had been advised to reply, and time and time again he had refused, always giving the same reason: his record would speak for him—the voters knew where he stood; he hadn’t changed; the voters would therefore know the charges were

false. And, naïve and unrealistic though this reasoning had seemed, time and again it had been proven correct—attack after attack had shattered against his image, in part because his image was so close to the truth that there were no cracks in which the charges could lodge; the charges had indeed been false, and the voters had indeed not believed them."

"But dignity was a luxury in a fight with Lyndon Johnson, a luxury too expensive to afford. Perhaps Stevenson had too much pride to deny the charge. Pride was a luxury that an opponent of Lyndon Johnson could not afford. Once Johnson found an issue, true or untrue, that “touched,” he hammered it—until people started to believe it. He had one that touched now; he had found the

jugular and he wasn’t letting go."

"Washington had learned of Lyndon Johnson’s gift for mimicry, of the accuracy with which he could capture a man’s traits and imitate and exaggerate them in a devastating form of mockery. Now he began to use that gift in the small towns of Texas on the man who had for so many years been a hero in those towns."

"Their absences for the campaign had cost the band’s four members their radio station job, but Johnson had told them not to worry: “Some day you’ll sing on the steps of

the White House.”"

* Johnson's and every salesperson's habit of promising without hard evidence or personal commitment.

"“He would urge you on,” Mashman says. “He had a knack of getting everything there was to get out of you.” "

Mashman had a unique view of what the pilot calls Lyndon Johnson’s “single-mindedness, his concentration, his determination”—

"Lyndon Johnson’s political genius had always enabled him to see opportunities for political gain where no one else saw them. He saw one now in Stevenson’s trip to his turf, and he had a reporter Stevenson trusted casually ask the former Governor to hold a press conference while he was in Washington. Sure, Stevenson said. "

"Johnson was well aware by now how Stevenson’s pride could be turned against him: since he would always refuse to defend himself against a hostile question, particularly one asked in an insulting tone, simply ask him a hostile question, and, when he refused to reply, accuse him of “dodging” the issue. The question Johnson was most anxious for Stevenson to appear to “dodge,” ............."

"Johnson wanted the whole press conference “abrasive,” and he made sure that other friends in the Washington press corps knew what questions to ask, and how to ask them. "

"in rapid-fire questions often couched in a sneering tone more suited to a prosecuting attorney interrogating an obviously guilty

defendant."

*Stevenson's backwardness in campaigning and pride was fully taken advantage of in the Senate race.

"The

Johnson campaign had between fifty and a hundred such delegates out on the road during the second primary and they each received between twenty-five and fifty dollars a day, plus expenses. Tens of thousands of dollars were thus spent to disseminate rumors about Coke Stevenson. Connally says the active campaigners were employed to “go around and spread propaganda. We’d contact a guy and give him walking money. To buy beers, that kind of thing. He’d just circulate, dropping these little tidbits. He’d go from beer joint to beer joint, and go into the Courthouses. He was a local guy, and no one would suspect he was employed in the campaign.”

"When Stevenson made his ‘notes’ reply, that was all we needed,” John Connally says. “Johnson had an issue. Mr. Stevenson’s strength came from his

appearance of being a very solid, stable, thoughtful man. And a man who was above politics. Now … he looked indecisive. He looked vacillating. And he looked political. Which was destroying his image."

"But when they saw Stevenson waver, they hated him worse than Johnson. To suspect that a former friend has betrayed you is worse than an enemy opposing you, and therefore they got very angry at

Coke.”"

LBJ- Book 2 Means of Ascent to the end:

*Destroying his opponent with propaganda:

"For the men who were no longer supporting Stevenson were the owners and

managers of corporations. “In those days, if a popular executive with a company let it be known he was supporting a candidate, a lot of the employees would go along. And now some of the companies we had expected to support us, weren’t.”"

"IN A FINAL TOUCH of irony, in Washington the presidents of four railroad unions endorsed Lyndon Johnson for Senator."

"MONEY COULD BUY more than publicity. Money could buy men. "

"Good, but brief—too brief to be effective. “Repetition—that was the thing,”"

Johnson had chipped and chipped away at Stevenson’s strength, but there was a solid core, a bedrock of belief in Coke Stevenson, that had not been touched.

Lyndon Johnson, Stevenson felt, had used the law against him, not the law in its majesty but the law in its littleness; Johnson had relied on its letter to defy its spirit.

notable lack of investigative and prosecutorial vigor.” An historian has written: “The FBI investigation … disappeared without a trace.” Attempts by

Stevenson partisans to interest the FBI and Justice Department more deeply in the case resulted only in “a fancy dance without a serious investigation”

"It is continuing evidence of the fact that not even his possession of

the presidency had eased the insecurities of his youth."

Now up to "Master of the Senate!"

This is reputably the finest book out of the 4 LBJ volumes.

I don't know how it can top Path to Power, which is already one of the best books I've ever read.

![]()

"When you come into the presence of a leader of men, you know you have come into the presence of fire; that it is best not incautiously to touch that man; that there is something that makes it dangerous to cross him.

—WOODROW WILSON"

Moses pg.615

"But Moses didn't need enactment to accomplish his purpose. He needed only delay. And he used all his vast influence in Albany to obtain it, keeping the bill bottled up in committee—and off Lehman's desk, where it could finally be disposed of—week after week"

"Before, his motivation had always been the work-the project, the achievement, the dream. Now the motivation was power"

"The vast amounts of money and power that vere obviously going to be involved made him even more determined to ceep the program firmly in his own hands. So Moses drew up his proposal n absolute secrecy—and presented it not to the Mayor but, in a bold ittempt to circumvent him, to influential private citizens; the very day after /oters approved the constitutional amendment, he persuaded several real estate and reform organizations to jointly rent the auditorium in the Museum )f Natural History for an evening ten days later and to invite several hundred key realtors and reformers to hear him give a speech. And he arranged to bring the program dramatically to the public at the same time"

"He may have realized that without protective coloration his attempt to move into a new, unrelated field would look like the barefaced power grab it was."

"the two officials realized that they were witnessing a public relations blitzkrieg—a lightning-like move by Moses to mobilize the opinion of the public in general and of the influentials in the audience in particular (his opposition to a real estate tax increase was a clever move to insure the support of the city's powerful real estate lobby) behind his plan so that the Mayor would not be able to overrule it"

Moses attempted to persuade the committee members to endorse at least some of his proposals, but La Guardia, working through Windels, the committee's chairman, made sure they didn't—by employing relentless pressure.

La Guardia handled all negotiations with Federal Housing Authority chairman Nathan Straus personally. He made all announcements of new projects from his own office, and in general made sure that Moses never knew what new public housing project was being planned until the planning was completed and the necessary federal funds allocated. Moses raged, publicly assailing the "secret, surreptitious" program, but he could not budge the Mayor.

by 1939, La Guardia would be pressing Moses hard indeed as to why he was not paying more attention to the suggestions of the Regional Plan Association. And beyond questions of parks and transportation, the Mayor had for some time been becoming progressively more aware of the question that a later generation would call "priorities." By 1938, he was acutely aware that the great strides made in parks and parkways were not being matched in any other areas of public works—not even in areas like schools and hospitals in which the need was desperate. "His feelings about Moses had subtly and gradually but substantially changed by the time I resigned as Corporation Counsel [in 1937]," Windels says. "He still felt he had matchless abilities and energies, but he also felt now that those abilities and energies must be channeled in the right direction if the city was to benefit from them.

"Of all the remarkable qualities of Robert Moses' matchless mind, one of the most striking was its ability to take an institution with little or no power, and, seemingly, with little or no potential for more power (at Yale, an unprestigious literary magazine; in state government, the Long Island State Park Commission) and to transform it into an institution with immense power, power insulated from and hence on a par with the power of the forces that had originally created it. And now the mind of Robert Moses had begun focusing on the institution known as the "public authority.""