Cult Icon

2585 replies · 37571 views

Moses pg. 640

". Legislators and mayor, as well as the city's citizens, continually reminded by the press of the long tradition that all its bridges be toll-free, had been assured that the tolls would be removed forever as soon as their cost had been paid for. "

"Tens of millions of dollars had been given him to hire men, but he had been required to hire them according to civil service regulations which

made it difficult for him—in most cases made it impossible for him—to hire the kind of men he wanted: the best men, the best engineers, the best administrators, the best ramrods, the best laborers. "

Under those regulations, he couldn't pay them enough to attract them to his service. He couldn't even hire whom he wanted of the men available at the salaries he could pay; he had to hire off civil service lists. ...

Civil service regulations made it impossible for him even to drive men as he wished to drive them: to drive men mercilessly you have to have threats to hold over their heads; the ultimate threat—dismissal—was all but denied him by the regulations; and dismissal for even a legitimate cause was a cumbersome and tedious procedure that had none of the efficacious effect on other workers of a snappy "Pick up your time and get out" from Art Howland or Earle Andrews. Civil service regulations had prevented him from using his men flexibly and efficiently"

" Most important, civil service regulations required him to hire men only for specific purposes approved by Legislature or Board of Estimate, and these purposes had never included the one most vital to his aims: long-range planning. For more than ten years he had been scheming, scraping and saving to build up a "stable planning force"—without success"

He would be able to attract to his service the men his sharp eyes had picked out of the herd, to hire and fire them as he pleased, to provide them with material rewards huge enough to make them endure his driving and his demands and to guarantee their absolute loyalty. And he would be able to hire men not only for specific but for general

purposes. He would be able to have, at last, his stable planning force."

"Moses knew were vital to Getting Things Done: the printing of impressive, persuasive brochures and pamphlets; the creation of large-scale dioramas and scale models ("It never ceases to amaze me how you can talk and talk and talk to some guy about something you've got in mind, and he sn't very impressed, and then you bring in a beautiful picture of it or, better yet, a scale model with the bridge all in white and the water nice and blue, see, and you can see his eyes light up," Jack Madigan says);

the hiring of public relations men to visit publishers, editors, reporters and radio commentators as well as nonmedia influentials, sell them on a project in advance, escort them on pre-opening limousine or yacht tours, leak them information that would place Moses' views in a favorable light (and his opponents' views in an unfavorable light); the rental of the necessary limousines; the hiring of the "bloodhounds" to dig up facts about an opponent that could induce him to cease his opposition, or, should he prove stubborn, could be leaked into print to discredit him; and, especially important to Moses because it gave him a chance to exercise his matchless charm as host, the laying on of hospitality—intimate luncheons for key individuals or lavish buffet luncheons for influentials by the hundreds— at which he could drape a big arm over a recalcitrant borough president's shoulders and use the glow induced by good food and fine wine to win him to his cause.

He had, of course, used his ingenuity, and his skill at circumvention of the spirit if not the letter of the law, to publish brochures, hire public relations men, purchase limousines and host luncheons in the past. But he had never had enough money to do all this as lavishly and effectively as he wanted. But let him keep the authorities' revenues and he would have enough"

Let him have the money—let him keep control of the authorities' revenues—and he, this man who had mastered the intricacies of civil service as well as any man who ever lived, would be able to devise a hundred ways to manipulate Civil Service Commission rulings to his own ends.

"Changing the law might give him more than money. Changing the law might give him power, more power than he had ever attained before. Money itself is power, of course, but the power he was thinking about now was power of far greater dimensions.

A public authority, he had learned, possessed not only the powers of a large private corporation but some of the powers of a sovereign state: the power of eminent domain that permitted the seizure of private property, for example, and the power to establish and enforce rules and regulations for the use of its facilities that was in reality nothing less than the power to govern its domain by its own laws. "

"The Legislature would never approve the bills Moses was drafting if they understood them.

So Moses would have to keep them—and all the other officials involved—from understanding. He would have to persuade Mayor, City Council, Legislature and Governor to approve his bills before they realized what was in them."

". If a single person in Albany or New York—Democrat, Republican, Governor, Mayor, assemblyman, councilman, any one of the thousand sharp-eyed lawyers who prowled the Capitol and City Hall— caught even a glimpse of his true aims, and sounded the alarm, he would never be able to accomplish those aims. He had to conceal his purposes from everyone."

"Moses, drafting amendments to the Triborough Bridge Authority Act, knew that the Legislature would never agree to the elimination of these safeguards.

So he didn't eliminate them.

He just made them meaningless."

""That sentence looked so innocuous. But it changed my whole act completely. With that sentence in there, he had power to issue forty-year bonds and every thirty-nine years he could call them in and issue new bonds, for another forty years. La Guardia had thought that authorities . . . would be temporary creations that would build something and then turn it over to the city and go out of existence as soon as it was paid off. But with that gimmick in there, it would never be paid off.""

"Previously, Robert Moses had always needed what he termed "execu the support." He had learned during his first great effort in public life—his attempt to reform the municipal civil service, an attempt brought to naught by ms betrayal by John Pur bel—that as long as he was an ap-

pointed official, he could not accomplish great dreams without the backing of die elected official who had appointed him. and he had never allowed to forget that fact His skill at bill drafting and his hold on the public had gained him a unique insulation from Mayors and Governors ms dairy operations, but it had still been only a chief executive who could give him die money and power necessary for the creation of giant public works"

Robert Moses still had all his old, immense, popularity. But were he, one day, to lose that popularity, the loss would no longer be nearly as disastrous as it would have been in the past. For no one—not the people, not the people's elected representatives, not the people's courts—could change those covenants

"Moses had what amounted almost to a horror of ceasing to build;...Only by continually embarking on new projects—which would require new bond issues—could an authority remain viable."

"Moses' methods—the methods with which he swayed politicians to his side—required secrecy. An authority gave him secrecy, for unlike the records of conventional governmental agencies, which were public, subject always to inspection, an authority's records were corporate records, as private as those of a private corporation."

""An institution," said Ralph Waldo Emerson, "is the lengthened shadow of one man." "

"The Mayor thought he knew how to handle so outrageous an attempt at intimidation."

"The Mayor could fire Moses as Park Commissioner, and thereby divest him simultaneously of his membership on those authorities. But this power existed in theory only; political realities made it meaningless."

" After reading the bond agreements and contn . La Guardia dropped all further discussion of the authorities' powers. Mi s never raised the matter again. But thereafter he treated La Guardia no 5 his superior but as an equal. In the areas o\ transportation and recreat . Robert Moses, who had never been elected b\ the people of the city to y office, was henceforth to have at least as much of a voice in determit g the city's future as any official the people had elected—including the Ma ."

* Moses placed himself in such a position where firing him would cause a blizzard of complications. He intentionally engineered the situation and entrenched himself too deep for the Mayor to fire

*Moses no longer needed elected office to get the money and power he needed to continue building. He didn't need public opinion so much anymore. The key was to see the potential for power where no one else saw them, act (with concealment) , and consolidate the defense.

Moses’ animating desire is to have an influence in the world. That is Caro’s point, I suppose – the author makes clear that this is a story about power, and what is “influence in the world” if not power?

But how much has Moses really changed? At the end of the day, his motivation seems to be exactly the same: How do I, Bob Moses, have influence in the world?

Put another way, when the arrogance of his ideas didn’t work, he simply shifted to the arrogance of power.

Moses' rageful response:

The sharp intelligence, superiority, personal detachment, the subtle threat, the obfuscation, and the pride in achievement, ...are all well represented in Moses’ response. But it gives a valued approach to his view of things.

http://www.bridgeandtunnelclub.com/detritus/moses/moses8.htm

"politicians were smart, and decided to play the game of delay, obfuscation and confusion. They focused on Moses since it was his plan and they made him a villain who was out to get rid of people who had earned their current position fairly. This played well with the press since they kept reporting the hardship the plan would cause to the affected workers and their family."

Moses pg. 678

"With the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel firmly in his grasp, Moses made a slight modification in its design: It became the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge.

The change reflected the importance Moses had come to place on bankers' values"

"a bridge was, after all, the most impressive of monuments ("the finest architecture made by man") as well as one whose life was "measureless";"

"Employing his usual strategy, Moses attacked not McGoldrick's arguments but McGoldrick. "What has happened since the application [certification] was signed, sealed and delivered by the Comptroller himself?" he demanded the next day. "What is behind the Comptroller's move and his swift change of front?"

It was the kind of attack that McGoldrick was later to admit "did intimidate people from debating with him—and intimidated me, too, quite likely." Moses knew perfectly well why he had changed his mind, the Comptroller was to tell the author. He had explained his feelings to the Park Commissioner at length. Moses knew there was no corrupt or sinister motive. But, he says, Moses certainly made it sound as if there was."

" but these old generals of reform had, as a rule, not been familiar with many of the locales in question and therefore had not been able to appreciate the objections to projects that were certainly worthwhile according to the theories in which they had been schooled. "

" although the techniques of the reformer—free and open discussion, persuasion, education—had caused him only disappointment (and were, over and over, to cause him disappointment again), he never abandoned them for the techniques of the politician. Robert Moses may no longer have believed that "the principle is the important thing," but Stanley Isaacs did."

"Throughout his career, Moses had charmed people he needed—and then, as soon as he didn't need them any longer, had turned on them.

He had always needed the reformers because he had always relied on public support, and they were in many ways the key to that support. But now, thanks to his discovery of the possibilities of the public authority, he didn't need public support any longer, and therefore he didn't need them.

And now, when they decided to fight his bridge proposal, he turned on them"

"In this arena the reformers had hope of success. Three councilmen were, after all, reformers themselves, nominees of the Fusion Party. Five were members of the American Labor Party, and organized labor favored a tunnel because it would furnish 2,600,000 man-hours of work as against 600,000 for a bridge. And all twenty-six councilmen were susceptible to pressure from civil service organizations angry as always at Moses because of his refusal to use civil service engineers on his authority jobs (he had recently stated it cost twice as much to do so), who wanted the more compliant Tunnel Authority to build the Crossing"

* When making demands, or offers, high ball it like crazy and adjust down as the negotiations clear up.

* Moses' method: attack the messenger a lot more than the message.

*Conceal weaknesses with distractions

*Moment of Truth

"The Battery Crossing fight was the moment of truth in their relationship with Moses. After supporting him for years in a score of battles, after sacrificing, over and over again, the principles so dear to them in his support, after helping to raise him to power and helping to keep him in power, they saw him at last for what he was—and they realized that he was not the embodiment of everything they believed in but its antithesis. If, for the twenty years before the fight, the Good Government organizations of New York City had supported him, for the twenty years after the fight, those organizations would oppose him"

"The Battery Crossing fight was also the'moment of truth for the reformers in another respect. It made them see that their opposition no longer mattered to Moses. They had played a vital role in his acquisition of power"

*Their voice no longer had power that they had previously thought:

" he had taken that power and used it to acquire more and more of it—and now, they suddenly realized, he had enough of it so that they could not take it back from him, could not, in fact, stop him from the absolutely untrammeled use of it. He no longer had to be concerned with their opinions—and he wasn't concerned with their opinions. "

"the only ripple, that revealed that far below the surface of the public controversy over Robert Moses' huge bridge, down in the quiet, murky depths, impenetrable to the public gaze, in which real power lurks, private passions were beginning

10 roil the water—and Robert Moses 5 great enemy was beginning to move against him."

Moses pg. 705

"Al Smith's close friend John A. Coleman, the multimillionaire "Pope of Wall Street" who came out of the Lower East Side with limited education but unlimited shrewdness, said: "Some men aren't satisfied unless they have caviar. Moses would have been happy with a ham sandwich—and power."

""Bob Moses could hate. If you stood up to him, he would hate you forever. If you defeated him, he would try to destroy you. Here were guys he couldn't destroy. So he decided to do the next best thing: destroy something they loved." "

"Moses' possession of unlimited powers over park administrative decisions made it possible for him simply to announce an "administrative decision" on Battery Park and the Aquarium: for the "safety of the public" they would be closed as soon as intensive tunnel work began, on October i, 1941, the park for the duration of such work, the Aquarium forever"

"Robert Moses, whose aim was not economic but political power but whose power would have to rest not on political but on economic factors, had understood that competition was a threat to his aims. He had schemed for ten years to remove that threat, to obtain over all modern water crossings"

". He went out of his way to avoid having to meet Singstad face to face. "

"For the Robert Moses about whom the Herald Tribune was editorializing hadn't existed for a long time. The Robert Moses of 1945 was not the foe of the practical politician but the essence of that peculiar animal. He was the complete realist. "

Moses pg. 715

"But, buried within the lines of convoluted legalisms, the amendment also contained an innocuous phrase—concealed, as was the custom of the man who had been the best bill drafter in Albany, at the end of a long sentence whose other clauses all purportedly limited his powers—allowing the Coordinator to "represent the city in its relations with cooperating state and federal agencies." Moses used this phrase, so innocent in appearance, as authorization to write into contracts between the city and these agencies provisions designating himself as the city representative with whom they agreed to deal, thereby making certain that it would be he and he alone who was presenting the city's position—or his representation of the city's position —on the design and relative desirability of construction projects to the two "outside" governments which would be largely funding them. The phrase also empowered Moses to negotiate with federal and state officials, learn their position and present that position—or his representation of that position —to city officials, to be, in other words, the sole broker between the city and the governments on which the city was relying for desperately needed funds. "

" the Democrats shrewdly making enough key Republicans a part of the arrangements by which the city was governed—putting them on the public payroll, giving them a share of judgeships and a cut of lucrative city contracts, taking them in as business partners—so that the GOP wouldn't try too hard to disrupt those arrangements, and so that when a private citizen, or the Citizens Union, or a newspaper, demanded an investigation of official corruption, no one with the power to conduct a real one was interested in doing so."

"New York was again what it had been before the Little Flower bounced into City Hall: a city in which everything had its price."

"Now the techniques were different: subtler, smoother. Charlie Murphy had taught his sachems that it was stupid to take cash, too easy for some prying reporter or rebel district attorney to trace it, too easy to prove that it had been taken in exchange for a favor, too easy to subpoena a contractor's books and haul the contractor's timid little bookkeeper before a grand jury and frighten him into telling what the items listed as "cash disbursements" really represented."

"Murphy and Plunkitt were uneducated men; they had never been to law school. If they had, they would have found the making of "honest graft" safer and easier still. Al Smith, as always, phrased it best. Strolling through a law-school library one day, the Governor noticed a student poring intently over his books. "There," he said with a smile, "is a young man studying how to take a bribe and call it a fee." By the Twenties, most honest graft was being worked through "fees," mostly through legal fees (more politicians belong to the legal than any other profession), but also through the real estate brokers' fees called "commissions," the insurance brokers' fees called "premiums" and the public relations fees called "retainers."

" It was the Retainer Regiment now. Corrupt public officials who were lawyers would support or oppose a bill according to the wishes of a business

firm, and later the firm would retain the official in his private capacity as an attorney, paying him a fee for "services"—legal services, of course—"rendered." Corrupt public officials who were insurance brokers would be allowed to write a firm's policies, and thereby to obtain the premiums attached. In the interaction of politics and public works, cash was now the medium of exchange only on the lowest levels."

Moses pg. 755

"Moses' personal reputation was reinforced by that of the institution with which, increasingly, it became blended. After as before the war, the public was being informed by Moses and by the press—in a single six-year period, 1946 through 1951, there were more than 1,400 editorials in metropolitan-area newspapers on this theme—that public authorities were not only "prudent," "practical," "businesslike" and "efficient" but "nonpolitical," "outside of politics" and therefore "honest." "Authorities are free from political considerations," the Times said. "They are free from the dead hand of partisanship and bureaucracy," the Herald Tribune said."

"the natural locus of corruption is always where the discretionary power resides."

"giving them unsecured loa which allow them to make investments without the inconvenience or ri of using their own money, and by giving them those loans at interest rat so favorable that the investments can hardly help resulting in a profit. Thi can give politicians loans of a size that make them rich beyond their drearr

The acceptance of these—and other—favors puts politicians in tl banks' debt. Banks are very good at collecting debts. They collect them wi interest. And they collect politicians' debts with interest: the public intere Decade after decade, what banks wanted from Albany or City Ha banks got."

"Banks have one aim: making money. Moses made sure their aim and h coincided. He made sure that banks would make money—quick money, eas money, safe money—from his public works.

Revenue bonds—the key to his authorities' existence and power—wei the key to the alliance"

"Moses' generosity to banks had to be paid for out of the pockets of motorists, of course. If bondholders received tens of millions of dollars extra in interest, drivers would have to pay tens of millions of dollars extra in tolls. The state's Public Authorities Law supposedly keeps the cost to the public of public works as low as possible by prescribing the use of open, competitive bidding on bond sales and all other details of authority operation. But Moses wasn't concerned with the cost to the public. His concern was to enlist in his cause the banks who could use their power to push behind-the-scenes political leaders, as well as state legislators, city councilmen, borough presidents—and Mayors and Governors—into approving a public work that they might otherwise not have approved. Open bidding would have defeated this purpose. Banks would not push hard for a public work if they knew that

after it was approved they would have to bid against other banks for its bonds—and might not get them at all. Banks would only push hard if they knew before the work was approved that they would profit from it"

And since the aim of the use of private placement was to place power behind his proposals, he selected as the favored banks those that had the most power to place there"

"When there is no work, construction workers blame their union officials. When there is no work for too long—and it is remarkable how short a period of time an out-of-work hard-hat can consider too lon^—': get themselves new union officials"

And, thanks to their political muscle, union leaders have vast influence over public construction. Union leaders are therefore constantly pressing for the scheduling of new public works. When employment is low. they are pressing for immediate ground breaking for new projects When employment is high. even when employment is full—even, in fact, when employment appears likely to be full for some years to come—they are pressing, having learned how long a "lead time" a large-scale public work requires, for the scheduling, planning and contract letting for future public works.

"Fees, retainers and commissions—the goodies of honest graft. Jobs and the endorsements, campaign labor and campaign contributions of organized labor. The contributions, untraceable and untaxable, of banks and contractors. These were the prizes that the individuals in the machine coveted and that the machine itself needed. And Moses controlled those prizes. Asked the secret of Moses' success, Lehman and Wagner adviser Julius Caius Caesar Edelstein replied: "My own theory? He was single-minded in his purpose, undeviating, merciless to those who opposed him—and he bought off everyone who might trip him up. He believed in buying, acquiring, by paying the most . . ." "Moses happened to be in the philosophy of replacing graft,"

"Several astute observers were to comment that it was through the telephone that power is exercised in New York. Men who felt the impact of Robert Moses' power often described it in terms of the telephone."

"They approached him for jobs, contracts and insurance policies as they had always approached him. And when he couldn't provide them, they viewed the failure as that of an individual, not of a system. They resented the failure, so much so that it would have had to be an insensitive borough president indeed not to recognize the danger to his chances for re-election. "They were indicted for a failure," a failure for which they were not at fault, Rodriguez says. There was a gap— a huge gap—between what people expected of them and what they could do."

Moses pg. 756

*Moses controlled about 60% of New York City's discretionary funds after his Tribough authority was established.

"The city simply did not have the money to build public works on the new scale required by the public—or by the greed of the political machines. But Moses' authorities—the authorities and the state and federal governments whose expenditures in the city he controlled—had the money. Through their seats on the Board of Estimate, the borough presidents had power—power to withhold street-opening permits, for example—to stop authorities from building. But the borough presidents did not have the power to build themselves. Their power was, therefore, negative only. They could deny, but they could not initiate. They could not provide what the people—and the county machines on which their own careers depended—were demanding. "

"His refusals with the Board were not as absolute as with the Council— the invitations of whose president he often declined even to acknowledge. In the first years after the war, in fact, while Moses was still testing the limits of his new-found strength, he did, while refusing to appear at public hearings of the Board, attend many of its closed-door executive sessions. "

"He centralized in his person and in his projects all those forces in the city that in theory have little to do with the decision-making process in the city's government but in reality have everything to do with it, and by such centralization he made them strong.

What were all these forces? Economic forces. "

"Under the system as it had existed before Robert Moses, these forces had been present in the decision-making process but had been to a degree subordinated to the force supposedly supreme in a democratic system of government. Moses mobilized these forces—whipped or enticed them into line behind his banner—so effectively that they and they alone were the forces that mattered, the forces that determined how the city would be shaped. He mobilized

economic interests into a unified, irresistible force and with that force warped the city off its democratic bias."

"The civic leaders who obtained pre-inaugural audiences impressed on him the need for new schools, hospitals, libraries, sewers and subways whose construction had been deferred by the war and by the prewar Moses monopolization of the city's resources."

and they were needed fast. But the city could not impose new taxes without permis-

sion from the state—and the state's Governor and legislative leaders, Republicans and up for re-election in 1946, were more interested in embarrassing than assisting him"

Bill Clinton reviews "Passage of Power"

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/06/books/review/the-passage-of-power-robert-caros-new-lbj-book.html

Moses pg. 806

"—but the more perceptive among them knew always that they were there not because of friendship but for a purpose, and that before the weekend was over, Moses would be putting his big arm around their shoulders and working for the vote, or the administrative decision, that he needed from them."

"If age could not wither his passion for work, sun—even tropical sun— could not bleach it. For years he had not taken vacations; now he did, if infrequently (generally in winter to the Caribbean), although it is notable that most of these vacations were to the luxurious island retreats of Bernard Gimbel or Robert Blum of Abraham and Straus or of other powerful men whose support he needed."

"And Tallamy not only was a man from whom Moses needed something but, as a federal employee, was not dependent on him for his salary. With men who were—the "Moses Men" who were his top executives and who were now virtually the only part of his empire with which he now dealt personally—Moses' impatience took other forms.

"If your answer wasn't fast enough for him, he'd get up and pace," Ernie Clark says. "If you told him you didn't know [the answer], he might say, 'Well, why don't you?' " And he didn't want to be bored with statistics; "he wanted conclusions and how you had gotten them." Once, a new engineering consultant began reading off page after page of statistics. Clark recalls that "Mr. Moses started pacing, almost like a caged tiger. And then he turned around and said: 'I never heard so much horseshit in my life.' "

"It wasn't that Moses didn't want money, of course. He wanted it desperately, as is proven by the commissions he continually accepted from magazines for articles he loathed writing, and by the eagerness with which he accepted $100,000 fees for arterial highway plans for other cities. But he had the Moses prodigality with money, the prodigality that had helped make his brother a pauper. He always accepted the $100,000 commissions with an idea of keeping a substantial portion for himself, but he always ended up using the money to buy other men who could help him in his New York work. "

* Moses' public works were skewed toward the needs of the wealthy as he needed to court their favor.

"Moses' answer was, reportedly, to the point. He threatened, as one reporter put it, to "reveal some facts that would greatly embarrass" the Democratic legislative leaders. "

But Moses' remarks had brought to a boil an Irish temper that had been simmering quietly for weeks. No dummy about bureaucratic maneuverings, he had begun to realize how cleverly he had been hemmed in with men whose first loyalty was not to him."

"Moreover, no immense intellectual capacity was necessary to see that the problems Moses had promised him would be solved so quickly were not being solved at all;"

The Board of Estimate, composed of men who had been listening to Moses' views for years,..."

"Finkelstein understood that O'Dwyer's natural friendliness, his tendency "to go along with the last guy" n to see him." made the Mayor a man easily swayed, or. as Finkelstein put it, "played"'—and, as he says, "I knew how to play BUI 0"Dwyer"; he had already played the Mayor into the vending machine concession for the city's subway stations."

To still them, eight separate times he denied that he was thinking of leaving office—once, on vacation in Florida, personally telephoning a New York Times editor to do so.

"He was too timid to confront even his own subordinates."

When Halley persisted in closely questioning Moses, or, more usually, since Moses himself seldom deigned to appear, Moses' deputies, during their appearances before the Council, Moses adopted a simple solution: he not only refused to discuss his programs with the Council himself but would not allow his aides to discuss them. And to Halley's frustration, the Council's Tammany majority approved those programs anyway

"The rule of reason was over. The rest of the city was going to be built by the law which had governed the building of the earlier parts: the law of the jungle.

And proof lay in Moses' relationship with the city's legislative bodies—the City Council and the Board of Estimate—already so effectively dominated by him through his use of the power of money."

rotected in general by civil service, the appointees would remain in their key, sensitive posts as new mayors sat in City Hall, knowing that mayors come and go, but that Moses remained—and that, therefore, in conflicts between Moses and a mayor, it was in their interest to give their loyalty to the former.

"There was, moreover, the momentum effect. Qualified administrators were scarce. Mayors were constantly engaged in a search for men with real experience in handling large-scale problems. The only way to get experience was to handle such problems, and since it was Moses' men who had been placed in positions to handle them, it was Moses' men—and sometimes only Moses' men—who were qualified.

More important than the men he installed, of course, were the stakes he drove. Once you get the first stake driven for a project, he had learned, no one would be able to stop it."

*Mayor Wagner never made derogatory comments about other people; he learned this from his father.

*Moses had a commonly used tactic of planting positions of influence with his plants/slaves.

Moses pg. 838

"Hospitality has always been a potent political weapon. Moses used it like a master. Coupled with his overpowering personality, a buffet often did as much for a proposal as a bribe. "Christ, you'd be standing there eating the guy's food and drinking his liquor and getting ready to go for a ride on his boat, and he'd come up to you and take both your hands in his or put his arm around your shoulders and look into your eye and begin pouring out the arguments in that charming way of his and making you feel like there was no one in the whole world he'd rather be talking to—how could you turn the guy down?" Ingraham knew what it meant when he was invited to a weekend in Babylon or a night at the Marine Theater: "He wanted to plant a story." To other reporters, too, his hospitality was used as a subtle reward, and its withdrawal as a subtle punishment. Write a story that he liked and you would find yourself on one of his lists—and, even on the "C" list, suddenly the need for paying causeway tolls would disappear and you would be able to bring your wife or girlfriend to lavish parties. Continue the good work and you might make the "B" list—or even the "A." Cross him once, and you were off all lists.

*Excellent social analysis, true to life:

"The setting at such luncheons was relentlessly social: friendly, easy, gracious. For most men, this setting made disagreement difficult. It is more difficult to challenge a man's facts over cocktails than over a conference

table, more difficult to flatly give the lie to a statement over a gleaming white tablecloth, filet mignon and fine wine than it would have been to do so over a hard-polished board-room table and legal pads. It was more difficult still to disagree when most if not all of the other guests agreed: there was strategy as well as ego in Moses' stacking his luncheons with a claque of yesing assistants; he may have felt that their presence heightened his stature but he also knew that their presence created an atmosphere in which the dissenter felt acutely that he was representing a distinctly minority view. To crack an especially tough opponent, Moses might invite him to a lunch at which he would be the only person present besides the Coordinator and his aides: then, if the guest tried to argue, he would be in the position of trying to argue alone against a whole platoon of "informed opinion."

It was even more difficult to disagree when the man with whom you were disagreeing was your host. Manners set limits on such disagreement; even if convention was disregarded, the host had the not inconsiderable psychological advantage of fighting on his home grounds, grounds to which, in fact, the guest might even have been transported by his limousine, which he needed to take him home again.

It was especially difficult to disagree when disagreement would touch off an argument, possibly a violent argument, with that host—and mosguests were well aware of the fact that the slightest disagreement with the host at Triborough was sure to start such an argument. If a guest still ventured to hold his opinion, there would be impatience.

The attitude was: "Well, well-informed opinion doesn't agree with you, does it? Does it, Sid? Does it, Earle? How about that, Stuart?" If the guest still did not back down, there would be not the uncontrolled, wall-pounding, inkwell-thro wing rage that could fill a room, but a mordant scorn that could slash across a dinner table like a carving knife. "He had a way about him, even strong men stayed away from him—he was the great intimidator," Joe Kahn says. Nowhere was he more intimidating than over his luncheon table. In such a setting, surrounded by pictures of his past successes, scale models of his future successes, by a retinue of supporters and all the trappings of achievement and power, his scorn and anger were at their most awesome.

An Austin Tobin might get up from his host's table, say, "I don't have to sit here and be insulted like this," and stalk out. Not many men had Tobin's courage, presence of mind—or the support of a board powerful enough to make courage and presence of mind feasible. In the setting Moses created at his luncheons, most men allowed themselves to be bullied, even if only by not openly disagreeing with some Moses proposal in the hope that they could disagree later in the friendlier confines of their office—only to find that before they could get out of his, Moses was virtually forcing them to ratify their acquiescence by presenting for their signature the necessary document, which an aide just happened to have with him, or to find out by the time they got back to their own office that Moses had already notified the Mayor or other department heads of their acquiescence and that the project in question had already been moved ahead to the next step, making an attempt to call it back awkward if not unfeasible. Casual, friendly, social occasions were not the best arenas in which to confront Robert Moses."

And Moses carefully kept the atmosphere social, even while using it for business ends. He would present a problem and his proposed solution to it, and then call on various of his engineers to present facts and figures supporting his arguments. Then he would say, with an easy, charming smile, "Well, since we're all agreed about this . . . ," and move on to the next item. "Well, maybe everyone there didn't agree," Orton says. "But in that setting, who could get up and start arguing? This was an exercise of power by assumption or inference. And it was damned effective." "So much got done at those lunches," says one of his aides. "He'd have a whole agenda —a whole list of items—and he'd go right through it. You might have two or three disparate groups there—each there about another item of business. And he would move from one to the other so easily, never letting one group know something that another group wanted kept secret. And at the end there would have been a dozen decisions [made]"—made as he wanted. "The city was supposed to be run from City Hall," Orton says, "but let me tell you I watched it year after year and I know: for years the big decisions that shaped New York were made in that dining room on Randall's Island." Hospitality—hospitality on an imperial scale—was one of Moses' most effective tools.

""the ancient truth that it is not knowledge but action which is the great end and objective in life, and that for every dozen men with bright ideas there is at most one who can execute them.""

"he was being honored, he would stand, while waiting for the applause to die down, with his arms folded across his chest, each hand grasping the opposite biceps, with his head tilted back. Taking a particularly important guest on a tour himself, he would speak in the imperial "we," but it was his gestures, sweepingly expansive,"

*Moses' deafness, insulation from opinion and new knowledge and zero time for reflection were the seeds of his defeat.

"He was making transportation plans based on beliefs that were not true any more. He was making plans that had no basis in reality"

LBJ III (Master of the Senate!)

"he was deceitful, and proud of it: at that moment, in the Democratic cloakroom, as he talked first to a liberal, then to a conservative, walked over first to a southern group and then to a northern, he was telling liberals one thing, conservatives the opposite, and asserting both positions with equal, and seemingly total, conviction. Tough politicians though some of the liberals were, they felt themselves bound, to one degree or another, by at least some fundamental rules of conduct; he seemed to feel himself bound by nothing; he had to win every fight in which he became involved, said men and women who had known him for a long time—“had to win, had to!”—and to win he sometimes committed acts of great cruelty"

"As President, conscious always of television, he tried to be what he conceived of as “presidential,” composed his face into a “dignified” (expressionless, immobile, carefully still) mask, spoke in deliberate cadences that he believed were “statesmanlike,” so that on television, which is where most Americans got to know him, he was stiff, stilted, colorless, unconvincing"

"ill was the last thing his face was then. The bold visage was as mobile as the face of a great actor; expressions—whimsical, quizzical, beseeching, demanding, pleading, threatening, cajoling—chased themselves across it as rapidly and vividly as if some master painter were painting new expressions on it; a “canvas face,” one journalist called it. It was a face that could be, one moment, suffused with a rage that made it a “thundercloud,” his mouth twisted into a snarl, his eyes narrowed into icy slits, and the next moment it could be covered with a sunny grin, the eyes crinkled up in companionable warmth. (Although there was, even in these moments, a wariness in those eyes.) He grinned a lot more often then, and he laughed a lot more often, and when he laughed, he roared, his mouth wide in a roar of laughter, the whole face a mask of mirth. And he was, when he needed to be, irresistibly charming, a storyteller with an extraordinary narrative gift"

"because he was a remarkable mimic, the legendary figures of Washington as well: when he imitated Franklin Roosevelt, a fellow senator says, “you saw Roosevelt”; when he imitated Huey Long filibustering on the Senate floor, there was Huey in the flesh. He was a teller of tales that not only amused his listeners but convinced them, for when a point needed to be made, he often made it with a story—he had what a journalist calls “a genius for analogy”—made the point unforgettably, in dialect, in the rhythmic cadences of a great storyteller"

"Still was the last thing his hands were. When, as President, he addressed the nation, they were often clasped and folded on the desk before him as if to emphasize the calmness and dignity he considered appropriately “presidential.” During his years as a senator, they were moving—always moving—in gestures as expressive as the face: extended, open and palms up, in entreaty, or closed in fists of rage, or—a long forefinger extended—jabbing out to make a point. Or they were making some gesture that brought a story vividly to life; Hubert Humphrey, recalling years later Lyndon Johnson explaining that “If you’re going to kill a snake with a hoe, you have to get it with one blow at the head,” said he would never forget “those hands that were just like a couple of great big shovels coming down.”"

"And, not on television but in person, he was, in the force of his personality, overwhelming."

". And all the time he would be talking, arguing, persuading, with emotion, belief, conviction that seemed to well up inside him and pour out of him—even if it poured out with equal conviction on opposite sides of the same issue; if Lyndon Johnson seemed even bigger than he was—“larger than life,” in the phrase so often used about him—it was not only because of the size of his huge body or his huge hands but because of his passions: burning, monumental. His magnetism drew men toward him, drew them along with him, made them follow where he led."

“I do understand power, whatever else may be said about me,” he was to tell an assistant. “I know where to look for it, and how to use it.” That self-assessment was accurate. He looked for power in places where no previous Leader had thought to look for it—and he found it."

And he created new powers, employing a startling ingenuity and imagination to transform parliamentary techniques and mechanisms of party control which had existed in rudimentary form, transforming them so completely that they became in effect new techniques and mechanisms. And he used these powers without restraint—as he did powers that had been used by Leaders before him, but that had seemed inconsequential because in their hands they had been used with restraint. Lyndon Johnson used all these powers with a pragmatism and ruthlessness that made them even more effective."

Power corrupts—that has been said and written so often that it has become a cliché. But what is never said, but is just as true, is that power reveals. When a man is climbing, trying to persuade others to give him power, he must conceal those traits that might make others reluctant to give it to him, that might even make them refuse to give it to him. Once the man has power, it is no longer necessary for him to hide those traits.

" It was not only men he bent to his will but an entire institution, one that had seemed, during its previous century and three-quarters of existence, stubbornly unbendable. Johnson accomplished this transformation not by the pronouncement or fiat or order that is the method of executive initiative, but out of the very nature and fabric of the legislative process itself. "

He was master of the Senate—master of an institution that had never before had a master, and that at the time, almost half a century later, when this book is being written, has not had one since

It took a Lyndon Johnson, with his threats and deceits, with the relentlessness with which he insisted on victory and the savagery with which he fought for it, to ram that legislation through.

Moses:

" If he was capable any longer of rethinking his policies, he gave no evidence of it. And because of his power, of course, there was nothing that could force him to rethink."

" People caught in intolerable traffic jams twice a day, day after day, week after week, month after month, began after some months to accept traffic jams as part of their lives, to become hardened to them, to suffer through them in dull and listless apathy. The press, responding to its readers' attitude, ran fewer hysterical congestion stories, gave fewer clockings. A city editor seeing a couple of reporters with their feet up on their desks on a slow Friday afternoon found other make-work than sending them out to discover how long it took to get from the Queens-Midtown Tunnel to the Lincoln Tunnel. Only in editorial columns— written, it sometimes seems, by men selected through a Darwinian process in which the vital element for survival is an instant and constant capacity for indignation and urgency—did the indignation and urgency endure. Traffic was still news, but it was no longer big news."

Moses- On information control:

"The difficulties were immense. Moses' relocation statistics had always been accepted. No city agency or newspaper had ever computed them even roughly for itself. There were probably over-all statistics in existence, of course, and brought together in one place—but the place was Randall's Island, and Randall's ruler kept the long rows of filing cabinets there locked. Many of the statistics were kept in the City Bureau of Real Estate, but the Bureau was under Moses' thumb; it was after attempts to obtain its statistics—supposedly public records—..

What statistics were available—often in obscure files, in other city agencies, of whose existence the unit would never have known were it not for Orton's encyclopedic knowledge of every corner of city government—were patently too low; Moses kept them low by refusing to count the actual number of people being evicted (instead he multiplied each "dwelling unit" by an "average" family size so small as to bear no discernible relation to reality), and by simply ignoring the existence of "doubled-up" families and boarders (of whom there are always a significant number in low-income areas) as well as of people living in rooming houses or hotels. (There is considerable evidence to suggest that the counts thus arrived at even after these omissions were arbitrarily reduced still further when Moses felt they sounded too high.)

Orton's unit could not repair these deficiencies. With the buildings in which these uncounted tenants had lived demolished and the tenants moved away, there was no longer any way of obtaining a record of their existence. Yet the unit did come up with a rough compilation: during the seven years since the end of World War II, there had been evicted from their homes in New York City for public works—mainly Robert Moses' public works— some 170,000 persons.

This total was almost certainly far too low. Orton, leaning over backwards as always to be fair and to make sure that the figures would "stand up" no matter what devices Moses employed to discredit them, leaned too far. He permitted his unit to make some adjustment in "official" figures, but not nearly enough to make them accurate.

"If the number of persons evicted for public works was eye-opening, so were certain of their characteristics.

Their color, for example. A remarkably high percentage of them were Negro or Puerto Rican. "

"If this picture of the past was disturbing, it paled before the picture of the future. Orton's staffers had assembled—for the first time—"statistics on the volume of tenant displacement we may expect in the foreseeable future." During the previous seven years, 170,000 persons had been evicted: a rate of about 24,000 per year. But Moses' slum clearance program was only now moving into high gear. During the next three years, 150,000 persons were scheduled for eviction: 50,000 per year. These people were mostly low-income Negroes and Puerto Ricans. "

Moses pg. 1,005

"But the Manhattantown revelations hardly touched Robert Moses at all. The fear and awe in which he was held by reporters, rewritemen, copy editors and city editors was never more evident than on the day following the Senate hearing on Manhattantown and in the days that followed. Robert Moses had conceived the Manhattantown project. He had directed its planning. He had selected the cast of characters who ran it. He had shifted the cast around when the political winds in the city shifted. It was a Robert Moses project from beginning to end. The Times story on Manhattantown did not mention Robert Moses once. The other papers followed suit. His name was hardly mentioned; no editorials called for his removal. There might have been scandal in Manhattantown, but Manhattantown's creator was unscathed by it.

And because he was, Manhattantown and the Title I program of which Manhattantown was a part were largely unscathed, too.

"The Times did not do another story on Manhattantown in the months that followed, but that might have been expected: the Times was not a paper of inquiry, and inquiry would have been necessary for follow-up stories. But what was not to be expected—from the customary behavior of the press in New York—was that no other papers would undertake any inquiry either. Not one investigative reporter was assigned to probe further into Manhattantown or Title I. Some reporters wanted to, but were refused permission" in some cases probably because of their publishers' admiration for Moses, in most cases simply because it seemed to editors a waste of time: where Moses was involved, they felt, there would be no scandal to be found; trying to find it would be a misuse of manpower that could be more profitably employed investigating politicians or bureaucrats. The creators of the Moses myth believed in what they had created. The myth still glowed, as strong as ever—with a glow that blinded New York to the shabby reality of what was going on on the Title I sites"

". The movement to reveal the truth about Moses' projects had been an underground movement, a movement led not by the City Planning Commission's majority but by the rebel commissioner Orton and his "fifteenth-story undercover" band of researchers, not by the city's reform housing "establishment" but by the new, boat-rocking Hortense Gabel. As late as April 1956, it was still an underground movement. "We were still voices crying in the wilderness," Orton recalls. "We couldn't get anyone to listen to us." A World-Telegram and Sun reporter managed to write a two-part series on relocation—a pallid, surface description that left the impression that all was generally well—without mentioning, even once, the man most responsible for relocation. Before the city could begin to see the truth about Moses' programs, his legend would have to be exposed for the lie it was. Before the people would be willing to look at Moses' programs straight on, they would have to look at Moses straight on, and before the public could do that, there would have to be an issue that would show him so clearly for what he was that there could be no mistake."

"The tactics Moses was using were the tactics he had been using for thirty years—but now the press was reporting them, and a whole city was watching them. The things Stanley Isaacs was saying now were the same things he had been saying for thirty years. The only difference was that now people were listening to them"

"The outrage the press expressed was echoed by the public. Letters not by the hundreds but by the thousands poured into newspapers and the offices of public officials; on a single day, Mayor Wagner received close to four thousand. And if the public was outraged, they knew precisely whom they were outraged at."

Thirty years before, Robert Moses had leapt onto the front pages in a single bound—in stories that portrayed him as a fighter for parks, as a faithful, selfless public servant, a servant whose only interest lay in serving, as a hero. This portrait, painted in an instant, had survived for thirty years and had hardened into an image that had withstood, without so much as a crack, a dozen explosions that would have shattered the image of the ordinary public figure. Now, in a single day, over a single dispute

a dispute over a hollow in the ground and a few trees—that image had

cracked. Not wide-open, of course. Large parts of it remained untouched; it was still an image untarnished by scandal, untainted by compromise; Robert Moses was still the public official uninterested in money, unwilling to truck with bureaucrats or truckle to politicians. But for the first time he had been portrayed to the public at large not as a defender but as a destroyer of parks and as an official interested not in serving the people but in imposing his wishes upon them. The image would never be whole again. Tuesday, April 24, 1956, the day that Robert Moses sent his troops into Central Park, was Robert Moses' Black Tuesday. For on it, he lost his most cherished asset: his reputation. The Moses Boom had lasted for thirty years. Now it was over"

" But whereas Moses had always used his image to make the press's bent for oversimplification work for him, now that bent was working against him."But other elements had been destroyed. No one who had followed the Battle closely could believe any longer that Robert Moses was in public life solely to serve the public. It had been all too obvious that what he wanted was to be not the public's servant, but its master, to be able to impose his will on it.

" Johnson as a virtuoso creator and user of power—every form of power, crude or subtle, blatant or disguised, cynical or sentimental."

I doubt that Caro, when he began his huge project, thought he would end up composing a moral disquisition on the nature of hatred. But that is what, in effect, he has given us. Hate breeds hate in an endless spiral. Clausewitz, discussing hate as the necessary fuel of war, says it is always on supply, since foes undergo a Wechselwirkung, a back-and-forth remaking of each other, one hostile act prompting a response even more violent, in a continual ratcheting up. That is what Johnson and Bobby are engaged in doing in this book; and Caro has given us many clues to their continued venomous interaction to come in his next volume.

"

"But still, the most significant fact about the series was that it ran at all. Investigative reporters quickly become aware of a phenomenon of their profession: information so hard to come by when they are preparing to write their first story in a new field suddenly becomes plentiful as soon as that first story has appeared in print. Every city agency has its malcontents and its idealists and its malcontent-idealists—officials and aides and clerks and secretaries unhappy with the philosophy by which it is being run or the payoffs that are being made within it—who have been just waiting, for years, for the appearance of some forum in which their feelings can be expressed. When they realize that there is one at last—when they see that first story— they cannot get their information to its writer fast enough. Scores of city employees—men and women angry for personal or philosophical reasons at the inside workings of the Moses empire—and hundreds if not thousands of city residents whose homes or neighborhoods had been destroyed for his

Title I projects, and who then had watched vainly for years for the projects to be built, had been looking for such a forum."

"

"Ordinarily, the tainting of a city program with scandal and failure—scandal of immense proportions, failure five years in duration— would result in at least curtailment of the powers of the mayoral subordinate heading that program, lest the public outcry turn against the Mayor. Their expectation was just based on a false premise: that Robert Moses was really the Mayor's subordinate. They did not understand that, as a matter of practical politics, the Mayor could not discipline, demote or remove Title I's administrator."

"Had he time to think about the situation, this realization might have come to him, but he had less time to think than ever. "

But fighting the press is a battle that no public official can win, for the battleground is not just of the press's choosing—it is the press. His attacks would be played as the media wanted them played. Moreover, attacking a particular newspaper—and because the articles were to a great extent exposes that were breaking in one paper at a time, his attacks were often against a specific newspaper—was practically the surest guarantee that that newspaper would attack him again in its turn. The story that had enraged

Moses may have been written by an individual reporter, but it was not the reporter alone who would have to bear responsibility for it and defend it to the publisher or chief editor. Lower-ranking editors—with stories of such significance, editors on several levels—would have had to apprc ve it. Therefore, when Moses attacked a newspaper publicly or in a private letter to its publisher, a lot of people on that newspaper had to justify themselves. And the most effective method of justification was to find other things wrong with the Title I program—and to write more stories. Many key newspapermen in New York had previously had a vested interest in preserving Moses' image; now many of these same journalists had a vested interest in destroying it. What was needed was discreet silence—the wait until the storm was over— and silence was one commodity it had never been within Moses' power to deliver.

The self-defeating nature of Moses' tactics was demonstrated in developments on the Times front.

Moses pg. 1067

"The Incorruptible, Uncorrupting, Apolitical, Utterly Selfless Public Servant Moses had been a synthetic character, largely puffed up by the press. That character had endured for thirty-five years. But in 1959 the process of deflation by the press—a process that had been going on intermittently for several years—had begun in earnest. In that process there had been a large amount of unfairness. But that process had in the end arrived at the truth. At the beginning of 1959, the Moses image had stood in most of its glory, intact except for a few small chips. At the end of 1959, it lay in unsalvageable ruins. Popularity, Al Smith had warned him, was a slender reed. Now the reed was broken"

". Power was derived from his Tri-borough Authority job, in which he measured his resources in hundreds of millions of dollars. He would be able to take the Fair job and still keep that. Power was derived from his chairmanship of the State Power Authority, in which his resources were also measured in the hundreds of millions, and he could take the Fair job and still keep that—as well as his other state posts: the Long Island State Park Commission presidency, the Jones Beach and Bethpage State Park authorities and State Council of Parks chairmanships. His appetite for power was undiminished. Shortly he would be seeking to take

over the development of atomic energy in the state because he saw that this was the new field into which money might be poured—his method would be the advocacy of laws placing all such development under his State Power Authority—but by trading in his city jobs for the Fair presidency, he would be giving that appetite more, not less, on which to feed."

"poisoning minds"

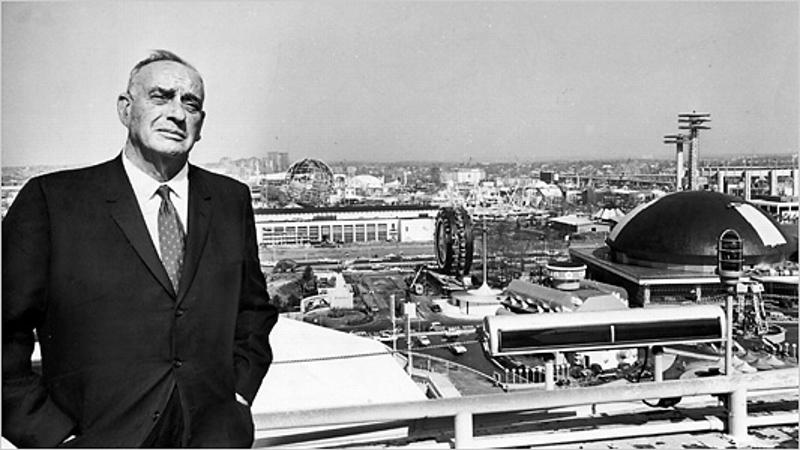

Moses' Stalingrad: The World Fair 1964/65:

The final battles: age 77 Moses, Old Lion, Young Mayor

"It wasn't rhetoric that was going to determine control of the transportation program in New York City, it was resolutions—the bond resolutions, the contract covenants of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. It wasn't polemics that were going to count in any confrontation; it was power."

"These men with their first taste of power laughed at him; he had not only tasted power but held it longer than many of these men had been alive. "

"These rash young men thought he was only Robert Moses of the World's Fair and Title I; he was also Robert Moses of Timber Point and Jones Beach and Hither Hills, of the Northern State Parkway and the Triborough Bridge and the Cross-Bronx Expressway and the Bay Ridge Approach. He was Moses of Massena, Moses of the Niagara Frontier. This was their first real battle; he came to it scarred with the wounds of a hundred battles—battles he had won."

Moses, THE END OF THIS MAGNIFICENT WORK!!!!

-The key element that removes Moses' power is his age. Mayors use it to blackmail him.

-Second is his arrogance- which lead him to blackmail and retire from 5 agencies.

-Third is his declining reputation do to public dissatisfaction, arrogant/contemptful PR, and finally, the World Fair fiasco

-Fourth, his ideas become old fashioned as decades pass and he does not have the time to reflect.

"Moreover, freed at last of the crush-

ing day-to-day political and administrative responsibilities, that intelligence was free to contemplate, to reflect. Moses' imagination—in shackles long to responsibility and ambition—was loosed again to dream and plan in leisure as it had dreamed and planned half a century before, when, with all other planners baffled by the urban recreation problem, it had, looking at Long Island, conceived a revolutionary solution. "

"What people didn't understand was that everything he had done was part of a plan, a dream—a plan planned and a dream dreamed decades before. Large parts of the plan were realized, but larger parts were not—including some of the most beautiful, some of the ones he most wanted to realize, some of the public works he had been trying to build for decades."

"e did not see the problem as a dichotomy but only as a failure on the part of public officials to understand the realities of the situation—that the public say on public works must be limited, and, in general, ignored, that critics must be ignored, that public works must be pushed ruthlessly to completion."

"The requests to have him speak slowed from a torrent to a trickle, and by 1972 had dried up almost entirely. The mail, once so huge a bundle three times a day, fell off to almost nothing"

"He was forgotten—to live out his years in bitterness and rage.

In private, his conversation dwelt more and more on a single theme— the ingratitude of the public toward great men. "

"Down in the audience, the ministers of the empire of Moses glanced at one another and nodded their heads. RM was right as usual, they whispered. Couldn't people see what he had done?

Why weren't they grateful?"

This is one of the finest and most enlightening books ever written, and in my top 10. There's nothing like it. I hope the plans for the HBO miniseries or films eventually get through. It is at once a biography, urban study, political science, management, and finally..history book. It has tremendous heart and insight into the human condition.

The original manuscript was 3,000 pages long- and will be published as a series.